The assassination of Spencer Perceval: what does The Gazette reveal?

Spencer Perceval is well known by most (pub quiz aficionados) to be the only serving

British prime minister to have been assassinated. But what do we know about the man

himself, and his political life, before that fateful afternoon in May 1812? And what

do we know of the vengeful John Bellingham, who shot the unsuspecting Perceval in

the heart in the lobby of the House of Commons, in ‘an act almost unexampled in the

annals of English history’ (Gazette issue 16612)?

Spencer Perceval is well known by most (pub quiz aficionados) to be the only serving

British prime minister to have been assassinated. But what do we know about the man

himself, and his political life, before that fateful afternoon in May 1812? And what

do we know of the vengeful John Bellingham, who shot the unsuspecting Perceval in

the heart in the lobby of the House of Commons, in ‘an act almost unexampled in the

annals of English history’ (Gazette issue 16612)?

Said to be of good character by contemporaries (if not, perhaps, by the general public), and a moderate Tory, Perceval was a family man not given to excess, who gave to charity and supported the abolition of the slave trade. In his memoirs, William Wilberforce wrote that Perceval 'was one of the most conscientious men I ever knew’.

The son of Irish peer, John Perceval, 2nd Earl of Egmont (Gazette issue 9369) and Catherine Perceval (nee Compton), the young Perceval was born on 1 November 1762. After being schooled at Harrow and graduating from Trinity College, Cambridge, he became a solicitor, studying at Lincoln’s Inn, London.

He is deputy recorder of Northampton in 1795

Perceval’s first appearance in The Gazette is on 17 November 1795 as deputy recorder of Northampton (a judicial officer), assuring loyalty to the sovereign following unrest in and around Westminster, ‘in gross Violation of the Publick Peace, to the actual Danger of Our Royal Person’ (Gazette issue 13833). This most likely refers to the preceding month’s events, when King George III had been pelted with stones during a time of disorders over the scarcity and high price of food (the Bread Riots).

Perceval had also been made commissioner of bankrupts in 1790, a role appointed by, and under the general superintendence of, the lord chancellor or lord keeper.

He becomes MP for Northampton in 1796

By his mid-30s, Perceval is elected, unopposed, as member of parliament for the town and borough of Northampton (which he held until his death) in the 1796 general election, and again in 1802:

‘Town and Borough of Northampton. The Honorable Spencer Perceval’ (Gazette issue 13899) and (Gazette issue 15498)

He attends the state funeral of William Pitt the Younger

In 1806, Perceval acts as emblem bearer at the funeral of William Pitt, prime minister (Gazette issue 15895). He described himself as a friend of Pitt above being a Tory.

He is appointed chancellor of the exchequer

Perceval was made solicitor general in 1801 and on promotion a year later, remained attorney general until Pitt's death. He held the position of chancellor of the exchequer from March 1807 until his death in May 1812, even while prime minister, through apparent lack of desirable (or available) alternative (Gazette issue 16015). He was also given the chancellorship of the duchy of Lancaster, to bolster his income.

He is appointed prime minister

In the same year as the King’s golden jubilee, the cabinet’s recommendation of Perceval as the new prime minister was accepted, and on 4 October 1809, he was appointed ‘the Right Honourable Spencer Perceval, Chancellor and Under Treasurer of His Majesty's Exchequer’ (Gazette issue 16312).

The Regency Act is passed to address the malady of King George III

The most notable legislation under Perceval’s premiership was the passing of the Regency Bill 1810 and the Regency Act 1811. Due to King George III’s worsening mental health following the death of his beloved daughter, Princess Amelia, the bill proposed the appointment of his son, the Prince of Wales, as Regent, but with restrictions for a year, during which time it was hoped that the King would return to health. The act gained royal assent on 5 February 1811 (Gazette issue 16451):

A Gazette extraordinary edition followed on 7 February 1811 (Gazette issue 16450), announcing members of the privy council and ‘His Royal Highness the PRINCE of WALES, Regent of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland’. The Prince of Wales continued as Regent until his father's death in 1820, when he was crowned King George IV.

He is assassinated by Bellingham

On 11 May 1812, while making his way to a committee in the Commons chamber, Perceval was shot in the heart by a pistol at point-blank range by John Bellingham, in an ‘atrocious act of assassination on the person of the Right Honourable Spencer Perceval, First Commissioner of His Majesty's Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer, within the walls of the Honourable House of Commons, on his way to the discharge of his important public duties’ (Gazette issue 16603).

Perceval collapsed and died soon after. Bellingham sat down and awaited his arrest. He was taken to a parliamentary cell overnight, before being taken to Newgate Prison.

Many loyal addresses to the Prince Regent follow

Loyal addresses followed throughout May and June on the melancholy occasion, expressing horror and indignation, along with the desire for punishment of the perpetrator of this ‘foul and barbarous deed’ (Gazette issue 16611).

High praise was given from the lord provost of Glasgow, John Hamilton: ‘Honourable Spencer Perceval cannot fail to excite in the bosom of every man who deserves the name of Briton’ (Gazette issue 16609).

The lord mayor of Cork, Thomas Dorman, stated that the king had been deprived of a 'faithful, zealous, and enlightened servant, and the country of a virtuous and upright minister’ (Gazette issue 16610).

Perceval’s cousin, Spencer Compton, becomes MP for Northampton

On 26 May 1812, Spencer Compton succeeded the late-Perceval as MP for Northampton: ‘Borough of Northampton: Spencer Joshua Alwyne Compton, commonly called Lord Compton, in the room of the Right Honourable Spencer Perceval, deceased’ (Gazette issue 16607).

An annuity is given to Perceval’s family

Parliament voted an annuity to Perceval's wife and 12 children the day after his funeral, after debate in the Commons concerning the amount. This was to make provision for his wife and help school the children, and in so doing, attempt to do justice to the services of their father, acknowledging that he was worse off as a public servant than he would have been as a lawyer.

On 13 June 1812, ‘An Act is passed for settling and securing certain annuities on the widow and eldest son of the late Right Honourable Spencer Perceval; and for granting a sum of money for the use of his other children’ (Gazette issue 16611).

The final Gazette mention of Perceval is on 10 July 1813, ‘An Act for confirming the renunciation made by Spencer Perceval, Esq. of his pensions, on his taking the office of a Teller of the Exchequer’ (Gazette issue 16751).

Perceval was buried in the family vault in St Luke's, Charlton, on 16 May 1812, in a private funeral, at the request of his widow. A marble memorial to Perceval by sculptor Sir Richard Westmacott (Gazette issue 19525) was placed in the nave of Westminster Abbey in 1822.

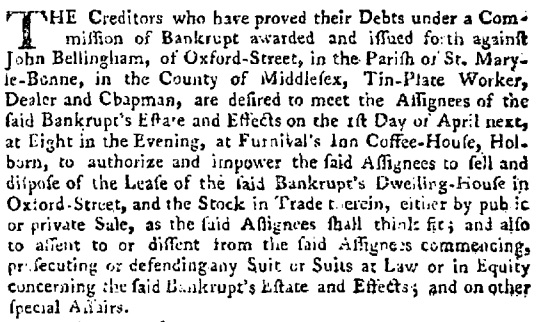

What does The Gazette reveal about John Bellingham?

Bankruptcy notice

The following 25 March 1794 bankruptcy notice is very likely to be that of the man who went on to assassinate the British prime minister in 1812 (Gazette issue 13635):

A notice for creditors’ claims for the same John Bellingham was published on 2 December 1794 (Gazette issue 13728), followed by a meeting of commissioners on 30 December 1794 (Gazette issue 13736) and a final dividend of estate and effects on 5 November 1796 (Gazette issue 13948).

Bellingham is said to have opened a tin factory on Oxford Street before he was declared bankrupt. He went on to become a clerk and then a merchant. After marrying Mary Neville in 1803, he went to the port of Arkhangelsk in Russia as an agent for importers and exporters.

Imprisoned in Russia

It was this John Bellingham, ‘an abandoned and infamous assassin’, ‘with diabolical and unfounded malice’ (Gazette issue 16605), who was arrested and imprisoned in 1804 for supposed insurance fraud while working in Russia. Bellingham had protested and attempted to impeach the governor general on his release a year later, and had pleaded with the British authorities for help. After an additional sentence was served, he was released, but without permission to leave Russia. He petitioned the Russian tsar and was permitted to leave in 1809.

Bellingham had spent five years in prison, in most likely appalling conditions, and was set on seeking reparation from the British government.

Seeking compensation

He returned to Britain in 1809 and worked as an insurance broker, spending three years requesting compensation from the British government – petitioning parliament, writing direct to Perceval and the Prince Regent, as well as the treasury and privy council – for this apparent wrong. Compensation was not given, and ministers refused to get involved or sanction his claims.

By now, the increasingly embittered Bellingham was set on more drastic measures, and purchased two pistols from a gunsmith in Skinner Street. He asked a tailor, James Taylor, to make adjustments to the inside pocket of a coat that would be nine inches in depth (to accommodate one of the pistols).

Exacting his revenge

On the afternoon of Monday 11 May 1812, Bellingham loitered in the lobby of the Houses of Parliament with two loaded pistols concealed under his coat. He had been a frequent visitor there in preceding few weeks, carefully observing members of the government.

Once the pistol had been fired, he made no attempt to escape.

Tried and executed

At his Old Bailey trial on 15 May 1812, presided over by Sir James Mansfield, Bellingham showed no regret for his crime:

“Finding myself thus bereft of all hopes of redress, my affairs ruined by my long imprisonment in Russia through the fault of the British minister, my property all dispersed for want of my own attention, my family driven into tribulation and want, my wife and child claiming support, which I was unable to give them, myself involved in difficulties, and pressed on all sides by claims I could not answer; and that justice refused to me which is the duty of government to give, not as a matter of favour, but of right; and Mr. Perceval obstinately refusing to sanction my claims in Parliament; and I trust this fatal catastrophe will be warning to other ministers.”

He admitted that he would as well have shot the British ambassador to Russia, Lord Leveson-Gower, had he been there – he saw both as representative of his oppressors. It took the jury less than 15 minutes to find him guilty.

On 18 May 1812, two days after Perceval’s funeral, Bellingham was hanged and his body carried away in a cart to St Bartholomew's Hospital to be anatomised. The only mention of his execution in The Gazette appears in the form of a threatening letter addressed to the Prince Regent that is published, with a reward offered for witnesses, that he [the Prince Regent] ‘will meet the same fate as Mr Percival if Billenghall [sic] is hung you shall be shot’ (Gazette issue 16605).

Over 200 years later, the Conservative member of parliament for North West Norfolk, Sir Henry Bellingham (Gazette issue 61230), is said to be distantly related to Perceval’s assassin.

Sources:

Garland J, Byways in History, Spencer Perceval: Britain’s only assassinated Prime Minister [online, pdf]

Old Bailey Proceedings Online, May 1812, trial of JOHN BELLINGHAM (t18120513-5), www.oldbaileyonline.org

The Parliamentary Debates from the year 1803, to the present time, Vol XXIII, 1812, London, Hansard

Images: 'Print showing Spencer Perceval (1762-1812), Prime Minister 1809-12 being assassinated by John Bellingham' and 'Portrait print showing Bellingham in profile published 1812' © Parliamentary Copyright