The Great Exhibition of 1851

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was probably the most successful, memorable and influential

cultural event of the 19th century.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was probably the most successful, memorable and influential

cultural event of the 19th century.

From May to October 1851, Hyde Park in London was filled with visitors to the ‘Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations’. The exhibition’s huge success confounded the predictions of its many doubters in parliament and the press: it was visited by over six million people (equivalent to a third of the British population at that date), and generated a vast profit of £186,000.

The 1851 exhibition was the first ever international exhibition of manufactured products. It inspired a long succession of international fairs in other cities, including Paris, Dublin, New York, Vienna and Chicago – almost one a year for the rest of the 19th century.

Origins

The Great Exhibition grew out of a series of very modest exhibitions of industrial design staged in London by the Royal Society of Arts. Leading figures in the society, notably its president, Prince Albert, the Prince Consort, and the design reformer, Henry Cole, hoped to stage something much more ambitious.

They were impressed in particular by the scale of the Paris Exposition of 1849, but they proposed an even larger event, which would be international in scope, where Britain’s engineering and manufactured goods could be compared with those of its international competitors. With Prince Albert’s energetic patronage, the necessary government support was secured, and in February 1850, the Royal Commission for the Exhibition advertised its initial plans (Gazette Issue 21071).

The Crystal Palace

The greatest challenge the commission faced was to design and construct a large enough exhibition building in a little more than 12 months. A design competition was staged, attracting nearly 250 entries, but all were rejected. The building committee’s attempt to produce its own composite plan was also unsuccessful.

Failure was averted by a proposal from Joseph Paxton, the brilliant head gardener at the Chatsworth estate in Derbyshire, who had designed a number of innovative glass houses for his employer, the duke of Devonshire. Paxton’s scheme (pictured right) was for a gigantic pre-fabricated building of iron and glass – nicknamed the ‘Crystal Palace’ by Punch magazine, and known by that name ever since.

Work on the building began in August 1850 and was completed in nine months. The only significant alteration to Paxton’s original concept was the inclusion of a barrel-vaulted section tall enough to accommodate three elm trees growing on the site, which would otherwise have had to be felled. A modular system of construction allowed the cast iron parts to be pre-fabricated in Birmingham, where the 293,000 panes of glass, the largest sheets ever made, were also produced.

The building’s remarkable statistics were proudly publicised and were even included in the inscriptions on the exhibition prize medals: 3,330 iron columns, 2,224 girders, 205 miles (330km) of sash bar and a glazed surface of 900,000 square feet (84,000m2).

The exhibition

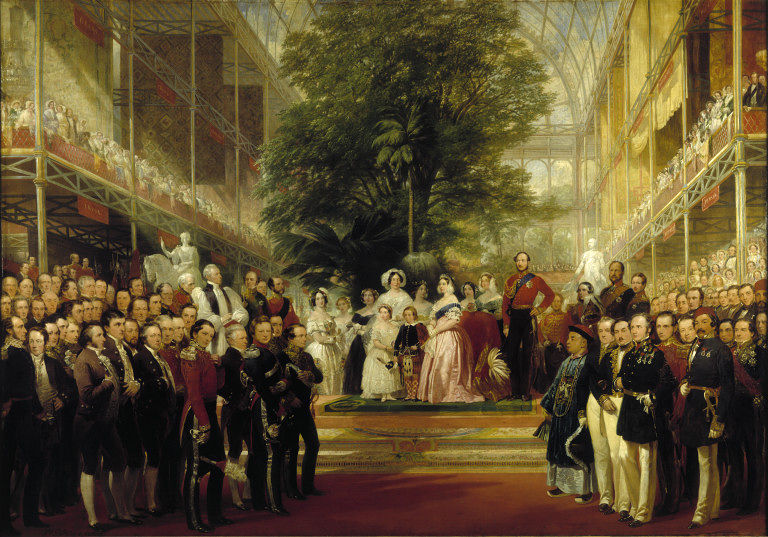

On 1 May 1851, exactly to schedule, the exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria (Gazette Issue 21208), accompanied by Prince Albert, other members of the royal family, politicians, diplomats and a crowd of more than 25,000 people. Over the next six months, visitors poured in to London from all over Britain, including groups of factory workers and agricultural labourers who arrived on excursion trains. Most of them (around 4,500,000) paid just a shilling (5p) to enter, though entry during the first three weeks and on Fridays and Saturdays throughout the exhibition was more expensive, and excluded less well-off visitors.

The western half of the Crystal Palace was devoted to Britain  and its colonies, and the eastern half to foreign exhibitors. The exhibits were broadly

grouped into four divisions: raw materials, machinery, manufactures and fine arts

(including architecture and sculpture, but not painting). Within these broad categories

a detailed classification system was used to arrange the exhibits and award prizes

– for example ‘Chemical and pharmaceutical processes and products’, ‘Civil Engineering,

architectural and building contrivances’ and ‘Woollen and worsted manufactures’.

and its colonies, and the eastern half to foreign exhibitors. The exhibits were broadly

grouped into four divisions: raw materials, machinery, manufactures and fine arts

(including architecture and sculpture, but not painting). Within these broad categories

a detailed classification system was used to arrange the exhibits and award prizes

– for example ‘Chemical and pharmaceutical processes and products’, ‘Civil Engineering,

architectural and building contrivances’ and ‘Woollen and worsted manufactures’.

Popular highlights of the exhibition included the fountain at the centre of the building, 27 feet (8m) high and made from four tons of pink glass; the Indian section (pictured right), which introduced visitors for the first time to the richness and quality of Indian textiles, but was particularly remembered for the howdah displayed on a stuffed elephant; the neo-gothic medieval court designed by AWN Pugin; the world’s largest known diamond, the Koh-i-Noor; ‘The Greek Slave’ (pictured below), a nude statue on a revolving plinth by the American sculptor Hiram Powers; and a collection of stuffed animals arranged in tableaux, such as kittens taking tea and a frog having a shave.

Legacy

The exhibition was closed by Prince Albert in a ceremony on 15 October 1851. The question of what to do with these huge but temporary buildings then had to be addressed. The Crystal Palace was bought in the end by a consortium of businessmen who had it re-erected near Sydenham Hill, south of London, where it housed concerts, festivals, exhibitions, and permanent displays of botany and art history. The building was completely destroyed by fire in 1936.

The cash profits of the exhibition were spent on establishing a new cultural quarter in South Kensington, sometimes referred to as 'Albertopolis', the home today of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Science Museum, Imperial College, Royal Albert Hall and other institutions.

Some of the exhibition’s legacy was more intangible: it had a real impact on art and design education, international trade and relations, and even tourism. The exhibition also set the precedent for the many international exhibitions which followed during the next 100 years.

About the author

Christopher Marsden is senior archivist at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Suggested further reading:

- The Great Exhibition, Victoria and Albert Museum [online]

- Gibbs-Smith, Charles Harvard, The Great Exhibition of 1851: a commemorative album. HMSO, 1950

- Jackson, Anna, Expo: International Expositions 1851-2010. V&A Publishing, 2008

- Leapman, Michael, The World for a Shilling: How the Great Exhibition of 1851 Shaped a Nation. Headline Books, 2001

Images © Victoria and Albert Museum, London:

- The Opening of the Great Exhibition by Queen Victoria on 1 May 1851, oil painting, Henry Courtney Selous

- The Great Exhibition building, architectural sketch, Joseph Paxton

- The Indian Court and Jewels, watercolour, Henry Clarke Pidgeon

- The Greek Slave, print on paper, George Baxter