Russian honours: Emperor Nicholas II of Russia

This article considers the centenary of two important honours that were conferred on Emperor Nicholas II of Russia during World War 1 – the rank of field marshal, and his appointment to be a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath.

Pre-war honours

By the start of the war, the Russian emperor held four high British appointments, as Queen Victoria had made him a Knight of the Garter (KG) and colonel-in-chief of a regiment, while his uncle had given him the Royal Victorian Chain and made him admiral of the fleet.

Nicholas received the Garter’s insignia in 1893, while he was in England to attend the wedding of his cousin, the Duke of York (later King George V) (Gazette issue 26423). Shortly after his accession to the throne, the emperor married Queen Victoria’s granddaughter, who became the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, and soon afterwards, he was appointed colonel-in-chief of the 2nd Dragoons or Royal Scots Greys (Gazette issue 26577), which had gained honours at Waterloo and later fought against the Russians during the Crimean War.

The position of colonel-in-chief was rarely conferred, although the German emperor had recently been appointed to the 1st Dragoons, and during Nicholas’s lifetime, the distinction was granted to other sovereigns, including the emperor of Austria and the kings of Spain and Denmark.

Nicholas’s uncle honoured his nephew with the Royal Victorian Chain in 1904 as a present to mark the christening of the tsarevitch (Gazette issue 27711). King Edward VII had created the chain at the time of his coronation as a special mark of royal favour, and by the time of the Russian ceremony, it was already held by several sovereigns, including the German emperor and the kings of Denmark, Italy and Portugal.

The Russian emperor wore the Garter, Scots Greys uniform and chain when he met King Edward in the Baltic off Reval (Tallinn) in 1908, an event that was marked with Nicholas’s appointment as an admiral of the fleet (Gazette issue 28145).

Field marshal

Six years after the Reval meeting Britain and Russia were united in war against Germany and Austria. While some of the emperor’s relatives forfeited their British honours – including the loss of Austrian and German Garters – important awards were sent to Russia to strengthen the alliance.

The New Year honours list of 1916 was headed by Nicholas’s appointment to be a field marshal (Gazette supplement 29424). The army’s senior rank had been granted to a few sovereigns in the past, although the precedents were unfortunate in light of what was happening in France and Flanders, as the German and the Austrian emperor had both received the British baton.

Nicholas’s insignia was delivered to him at the imperial headquarters in February 1916 by General Sir Arthur Paget, who said (The Times, 2 March 1916, page 6):

‘By command of his Majesty the King, I have the honour to present your Imperial Majesty with the baton of a Field-Marshal of the British Army. My August Sovereign trusts that your Majesty will receive it as a token of his sincere friendship and affection, and as a tribute to the heroic exploits of the Russian Army.

‘Though the distance which separates them has rendered it as yet impossible for the Russian and British Armies to fight shoulder to shoulder against the common enemy, they are united in the firm determination to conquer the enemy...

‘The British Army, who share his Majesty’s admiration for their Russian comrades, welcome your Imperial Majesty as a British Field-Marshal, and the King is confident that the Russian and British Armies, in conjunction with their gallant Allies, will not fail to secure for their countries a permanent and victorious peace.’

Order of the Bath

The emperor’s second honour of 1916 was the Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB), which was intended to recognise the work of the imperial navy, just as his field marshal’s baton had provided a tribute to the ‘heroic exploits’ of the Russian army.

In line with a practice that was introduced towards the start of King George V’s reign, in connection with the appointment of foreign candidates for British honours, the imperial Russian honour was not published in The London Gazette.

The Bath insignia was delivered by the British ambassador, Sir George Buchanan, whose address at the imperial headquarters in October 1916 referred to the naval situation (The Times, 20 October 1916, page 7):

‘In spite of the great numerical superiority of the German Fleet, your Majesty’s Baltic Fleet has repulsed with loss all its attacks on Riga, has carried out successful raids, and barred its entrance to the Gulf of Finland. Like the British Fleet in the North Sea, your Majesty’s Fleet has kept watch and ward in the Baltic and, though still unable to fight in line, the two Fleets are acting together in close cooperation.

‘British submarines, moreover, have penetrated into the Baltic, where they are proud to fight under the orders of the Commander-in-Chief of your Majesty’s naval forces in those waters.

‘In the Black Sea the Turkish Fleet, reinforced by the Goeben and Breslau, after several unsuccessful encounters with your Majesty’s ships, have been driven into the Bosporus.

‘In recognition of these services, and as a tribute of his admiration of the Russian Navy, the King has commanded me to present to your Majesty, as Commander-in-Chief of your Majesty’s land and sea forces, the insignia of Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, Military Division.’

The senior grade of the Order of the Bath had rarely been given to Russians before Nicholas was appointed. The precedents included a civil GCB for Nicholas’s uncle, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, at the time of Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee celebrations (1887), and military GCBs for the emperor’s brother, Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich (1901) and his more distant cousin, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich (1915).

Three of the Romanov GCBs met a violent end, as Sergei was assassinated in Moscow in 1905 and Nicholas and his brother were killed by the Bolsheviks in 1918.

Russian legacy

Nicholas abdicated in March 1917 and was later murdered at Ekaterinburg.

Sir George Buchanan – the ambassador who delivered the GCB insignia to the emperor in October 1916 – played a role in conveying news of the emperor’s fate to King George V, which he did at Buckingham Palace in the summer of 1918:

‘For his audience after the Council he [Buchanan] had a letter from a Russian, whose credibility he could trust, recently returned from the country, giving the first authentic narrative of the Tsar’s death, including an incident which points to his son having shared the same fate. According to this story, the Tsar’s execution was solely dictated by the fear of the Soviet that Czecho-Slovack forces approaching Ekaterinburg would liberate their prisoner. .... He was conveyed to the Riding School, where he met his death with great composure and determination, refusing to have his eyes bandaged, and merely pleading for the lives of his wife and children.... With this act of sanguinary brutality the curtain falls upon the dynasty.’

Nicholas’s connection with the Order of the Garter is recalled today in the heraldic plate which remains in St George’s Chapel at Windsor, while his association with the Royal Scots Greys was remembered in 1998, when the regiment was represented as the remains of the imperial family were laid to rest in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St Petersburg.

The legacy of Russia’s imperial orders survived in Britain for many years after the emperor’s death, as The Gazette reported permission being granted to British personnel to accept insignia they received from Petrograd in connection with services rendered during the war.

Recipients of such honours included Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, the commander-in-chief in France and Flanders, who received the Russian Order of St George, while the fourth class of the Order of St Vladimir was given to Prince Albert, who wore his imperial badge both as the Duke of York and later as King George VI (Gazette supplement 30108). The St Vladimir insignia was also given to Prince Alexander of Battenberg (later Marquess of Carisbrooke) (Gazette supplement 30116), who met his Russian cousin for the first time at Balmoral in the 1890s and was the last grandson of Queen Victoria when he died some 40 years after the curtain fell on the Romanov dynasty.

About the author

Russell Malloch is a member of the Orders and Medals Research Society and an authority on British honours.

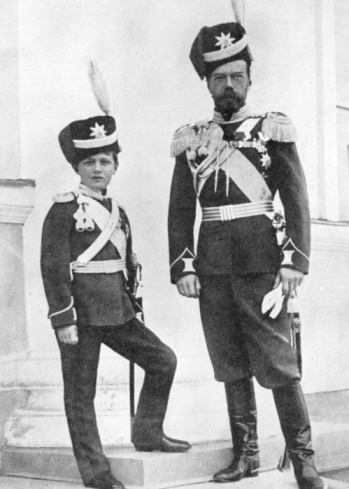

Pictured: Nicholas II with son, Alexei