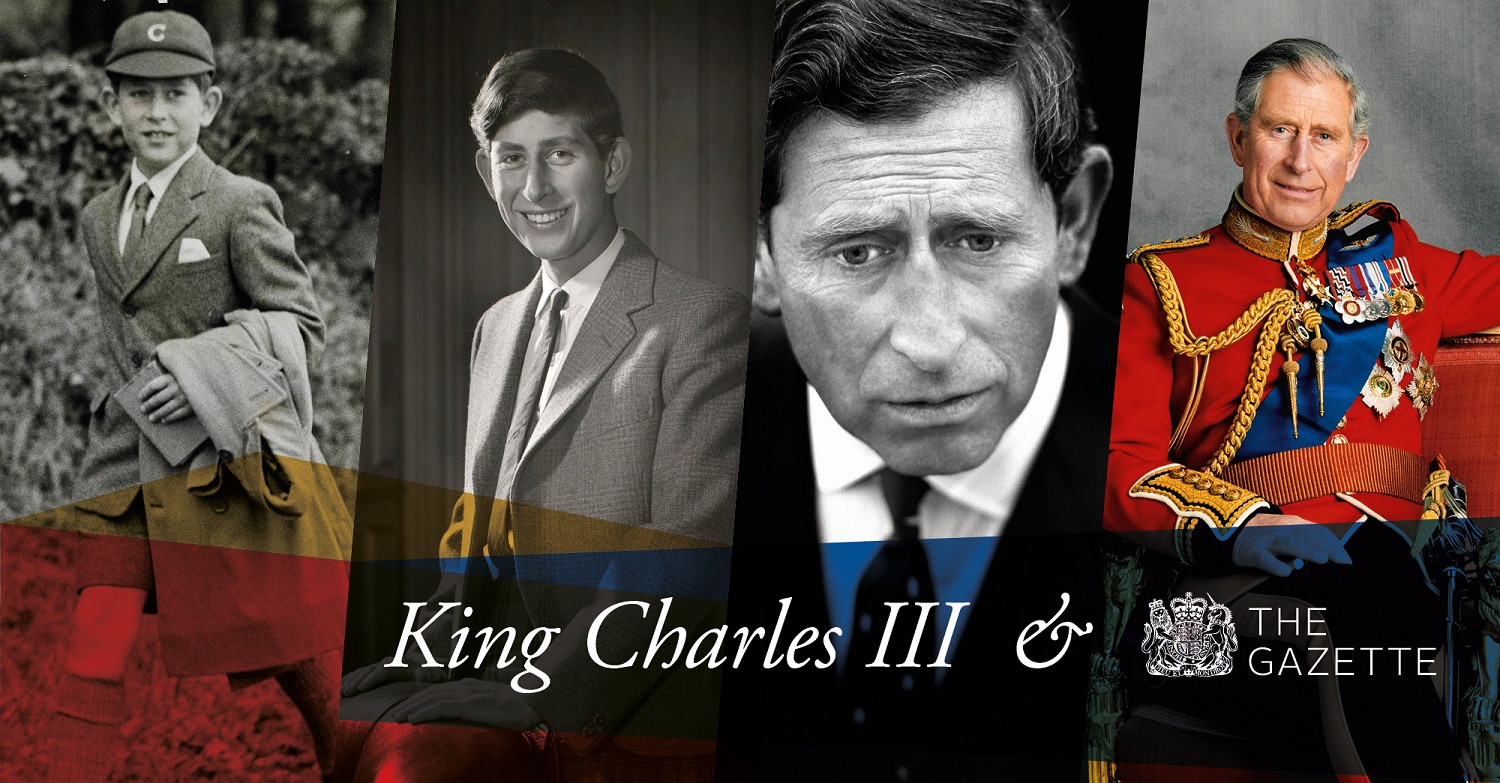

King Charles III and The Gazette: Family matters

Ahead of the coronation due to take place on Saturday 6 May 2023, historian Russell Malloch examines aspects of the new King's life that have left a record in The Gazette. In this chapter, we look at the births, marriages, and Cornish and Scottish titles of Charles III.

Chapters

Infant Prince

The events in the King’s life that feature in The Gazette start with the official record of his arrival as the first grandchild of King George VI, after Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh gave birth to a son at Buckingham Palace on the evening of 14 November 1948 (Gazette issue 38455).

Notices about the birth of royal princes and princesses had many precedents, as in June 1688 when readers of The Gazette learned that James II’s son was born at St James’s Palace, and that the King had knighted his wife’s physician (Gazette issue 2354). The Gazette did not identify the team who attended Princess Elizabeth in 1948, although the Court Circular listed the personnel who signed the statement about her son’s birth, consisting of Sir William Gilliatt, Vernon Hall, John Peel and Sir John Weir.

The Gazette also reflected work that was done in anticipation of the birth. Letters patent were issued on 22 October 1948 to regulate the style and titles of “the children of the marriage solemnized between Her Royal Highness The Princess Elizabeth and His Royal Highness Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh”. The patent determined that they should “have and at all times hold and enjoy the style title or attribute of Royal Highness and the titular dignity of Prince or Princess prefixed to their respective Christian names in addition to any other appellations and titles of honour which may belong to them hereafter.” (Gazette issue 38452)

This patent provided the authority for the King’s grandson to use the prefixes Royal Highness and Prince, which he did from the time of his birth until his succession to the Crown.

Prince Charles

The prince was christened at Buckingham Palace on 15 December 1948, and was given the names Charles Philip Arthur George:

- Charles was the name of two of the 17th century’s Stuart kings, and was given to three sons of James, Duke of York (later James II), including the Duke of Cambridge who survived for only a few months in 1677 (Gazette issue 1250). It was also used by one of the prince’s sponsors from 1948, as King Haakon VII’s name was rendered in English as Prince Charles of Denmark until 1905 when he accepted the offer of the Norwegian throne.

- Philip was the prince’s father, and a name that was not widely used in the British royal family before 1948.

- Arthur was given to several princes, initially in memory of the soldier and statesman Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. The most notable royal Arthur in the recent past was Queen Victoria’s son who became Duke of Connaught and died in 1942, and was one of Prince Charles’s predecessors as the great master of the Order of the Bath.

- The child’s last name of George was adopted by six British kings, starting in 1714, and was more recently used by two of the prince’s sponsors, his grandfather King George VI and his great-uncle Prince George of Greece.

The prince’s fourth male sponsor was his maternal uncle, David Bowes-Lyon, while his four female sponsors consisted of his great-grandmother Queen Mary and his aunt Princess Margaret, together with the Dowager Marchioness of Milford Haven (formerly Princess Louis of Battenberg) and Lady Brabourne (later Countess Mountbatten of Burma).

The prince was usually known by his first name, and it was the one by which he chose to be styled when he came to the throne as King Charles the Third.

Marriage

The next important personal event was the prince’s marriage. This was preceded by a meeting of the Privy Council at Buckingham Palace on 27 March 1981, when the audience included past and present prime ministers Alec Douglas-Home, Harold Macmillan, Margaret Thatcher and Harold Wilson, and the Queen formally consented to her son’s union with Lady Diana Spencer, as required under the Royal Marriages Act 1772 to prevent the contract of matrimony from being null and void. (The 1772 statute was repealed in 2013, when the marriage provision was replaced by the Succession to the Crown Act, which had a more limited scope, and only applied to the six persons next in the line of succession, rather to than any descendant of King George II.)

The Windsor-Spencer wedding took place in St Paul’s Cathedral in London on 29 July 1981. The Gazette did not reproduce the ceremonial, and so followed the practice in 1923 and 1947 when the prince’s grandparents and parents were married in Westminster Abbey. This contrasted with the earlier reporting of royal unions, such as the marriage of the Duke of York and Princess May of Teck (later King George V and Queen Mary) at St James’s Palace in 1893 (Gazette issue 26424).

The Gazette detailed some of the measures that were taken to mark the wedding. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office announced that the Queen had approved a temporary relaxation of the rules governing the commercial use of royal photographs on articles which were manufactured specially as souvenirs of the marriage, and the Prince of Wales approved that certain of his arms, cypher and portraits could be used (Gazette issue 48545).

The Gazette also published the proclamation that was made under the Coinage Act 1971 on 10 June 1981 to determine the design of the 25 pence coins that were to be struck to celebrate the marriage, which carried portraits of the royal couple (Gazette issue 48638). There was no statutory requirement for any proclamation to regulate the commemorative stamps that were issued by the Post Office.

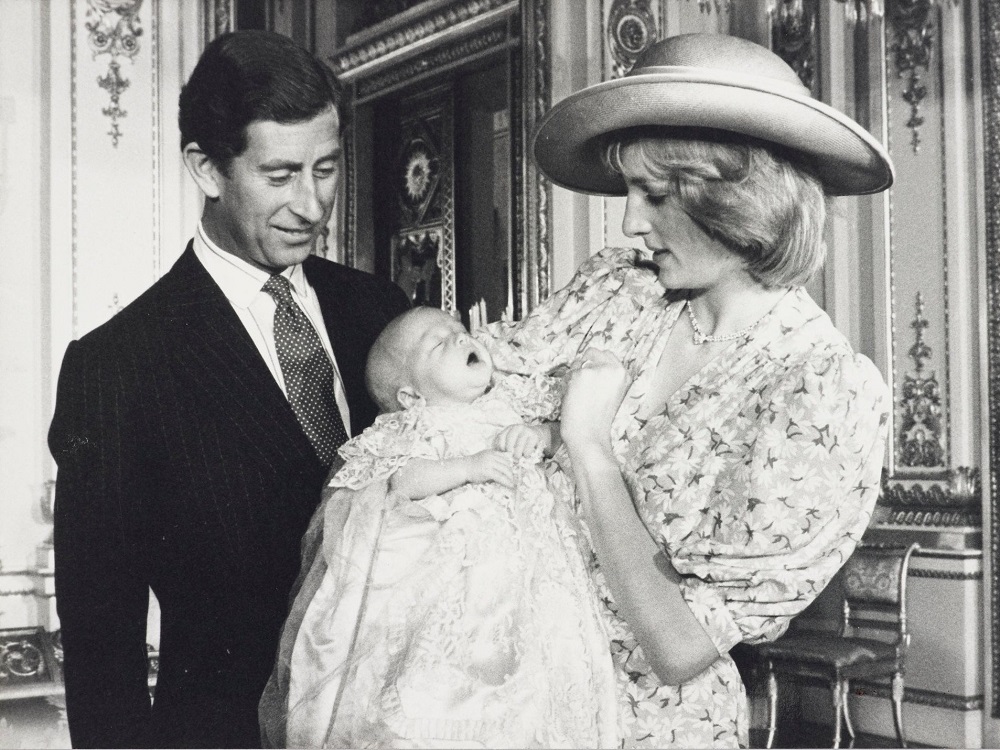

The birth of the couple’s sons was gazetted, with news about the arrival of Prince William at St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington in June 1982 (Gazette issue 49027), and then Prince Harry in September 1984 (Gazette issue 49869).

The marriage ended in divorce, and The Gazette set out the rules that would regulate the prefix that could be used by former royal wives, which would soon apply to Diana Spencer. Letters patent of 21 August 1996 declared that a former wife (other than a widow, until she should remarry) of the son of a sovereign, or of a son of a son of the sovereign, or of the eldest living son of the eldest son of the prince of Wales, would not be entitled to hold or enjoy “the style, title or attribute of Royal Highness” (Gazette issue 54510).

As regards later developments, The Gazette was silent about the marriage of Prince Charles and Mrs Camilla Parker-Bowles at the Guildhall in Windsor on 9 April 2005, but it did report the birth of four of the prince’s grandchildren, with the arrival of Princes George and Louis and Princess Charlotte of Wales, and Lord Archie Mountbatten-Windsor (Gazette issue 60576, Gazette issue 62265, Gazette issue 61216, and Gazette issue 62640)

The Gazette also recorded three proclamations relating to the issue of coins to mark the prince’s birthday. The first came in December 1997 and described a series of £5 coins for the 50th birthday (Gazette issue 55036), which combined the prince’s effigy with the words “The Prince’s Trust” and “Helping young people to succeed” to reflect the work of an organisation that he used to engineer social change.

Similar coins were struck for the prince’s 60th and 70th birthdays. The proclamation of October 2007 established £5 coins of different metals and finishes, sharing a common reverse with a profile portrait, the prince’s motto Ich Dien (“I serve”), and the years 1948 and 2008 (Gazette issue 58479). The final provision from March 2018 reflected the Royal Mint’s changed commercial focus, as it included platinum coins that were designated as legal tender, which all showed “a depiction of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales” (Gazette issue 62238).

Heir apparent

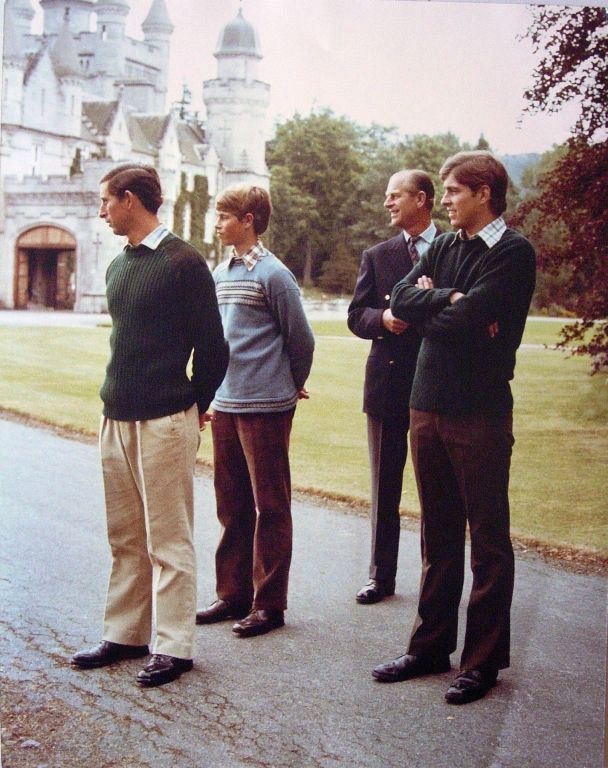

The birthday coins all referred to Charles as Prince of Wales, but during the reign of his grandfather he did not receive any honours beyond the styles of prince and royal highness, and did not gain the Welsh dignity until his mother was on the throne.

This reflected the fact that the Duchess of Edinburgh was only the heir presumptive to the throne in 1948, rather than the heir apparent. It was therefore possible, although unlikely, that George VI could have a son who would automatically become duke of Cornwall and duke of Rothesay, and so displace Princess Elizabeth and her children under the existing law of succession.

The prince’s status changed because of the death of his grandfather on 6 February 1952, when his mother succeeded to the Crown as Queen Elizabeth II, and he became the heir apparent (Gazette issue 39458).

The Gazette reported several measures connected with the Queen’s accession but contained no notices about the issue of letters patent or similar formal documents conferring the dignities that Prince Charles gained as heir apparent, as (following long-standing precedent) he became duke of Cornwall in the peerage of England, and duke of Rothesay, earl of Carrick and baron of Renfrew in the peerage of Scotland.

He also received the titles of lord of the Isles and great steward of Scotland, which reflected his family’s ties with the northern kingdom but which, like the three peerages, involved no estates or assets associated with Rothesay, Carrick, Renfrew or any of the Scottish islands.

Duke of Cornwall

The absence of estates relating to the prince’s Scottish titles contrasted with the situation in England, where the duchy of Cornwall provided an income for the current holder of the peerage and derived from a private portfolio of assets. Those assets began to be formed in the 14th century and were later regulated by parliament through a series of Duchy of Cornwall Management Acts.

The assets were spread across 20 counties in England and Wales, rather than being restricted to Cornwall, and included the Isles of Scilly, land on Dartmoor, the Highgrove estate, and urban developments at Nansledan and Poundbury. The duchy holdings had a net value of just over £1 billion by March 2022.

The duchy’s financial standing was an important element in the statutory provisions that regulated the public and private sources of wealth to which the reigning sovereign had access. What was termed the hereditary revenues of the Crown even featured in King Charles’s accession declaration in September 2022 (Gazette issue 63812).

The earliest statute to deal with this matter during the prince’s lifetime was the Civil List Act, which received royal assent in August 1952. This followed legislation that was promoted at the start of each reign, under which the sovereign received funds from Parliament to maintain the royal household, in exchange for part of the hereditary revenues. The yearly sum payable under the 1952 act was set at £475,000, and was reduced by amounts reflecting the net revenues of the duchy of Cornwall, if the duke was a minor, or if the duchy was vested in the Queen.

Further changes were made by the Civil List Act of 1972, which increased the Queen’s annual payment to £980,000, while the duchy’s income continued to be a relevant factor when the civil list provisions were replaced in 2011 by the sovereign grant, which was designed to provide resources to support the Queen’s official duties, and was set at £31 million for the financial year 2012-13.

Of greater financial importance to the well-being of the royal family was the duchy of Lancaster, which continued to be vested in the reigning sovereign rather than the heir to the throne. The duchy owned a historic portfolio of land and other assets, including the Savoy estate in London, which had a net value of around £650m by March 2022. The portfolio is held trust and continues to provide the monarch with a source of income that is independent of government, although in circumstances that are subject to statutes going back to the Crown Lands Act of 1702 that placed constraints on the management and administration of the duchy and its assets.

Prince Charles was seldom referred to in the Court Circular or in any other official settings by his original titles of Cornwall or Rothesay, except when he was involved in engagements in the south-west of England or in Scotland.

The Court Circular often used the prince’s Cornish title when he attended meetings about the duchy estate, and when he and his second wife – who was styled the duchess of Cornwall from the day of their marriage in 2005 – travelled to places such as Nansledan and Poundbury, the extensions to Newquay and Dorchester that embodied the principles of architecture and urban planning that were championed by the prince.

Notable visits to the south-west include those in July 2008 when the St Mawes ferry was officially named The Duchess of Cornwall; in July 2010 when the prince presented Operational Service Medals and met personnel from Royal Naval Air Station Culdrose on the Lizard Peninsula; and in June 2022 when, as patron of the Royal Cornwall Agricultural Association, he attended the Royal Cornwall Show at Walebridge to mark the 70th anniversary of becoming duke of Cornwall.

The duke’s Cornish coat of arms became familiar to a wider audience in the 1990s, when his coronet and ducal arms (including a black shield with 15 bezants or gold circles) were used for marketing purposes by Duchy Originals Limited. This company produced a biscuit made from cereals grown organically at the prince’s home at Highgrove in Gloucestershire, and later licensed the duchy brand to Waitrose & Partners, with profits being donated to the Prince of Wales’s Charitable Foundation, whose aim was to transform lives and build sustainable communities.

Duke of Rothesay

The prince’s Scottish titles were usually adopted while he was in Scotland. In September 1998, for example, the Court Circular explained that he visited Rothesay Castle on the Isle of Bute to mark the 600th anniversary of the first granting of the ducal title to the son of King Robert III, and then crossed the Firth of Clyde where, as Baron Renfrew, he attended a reception at Renfrew Town Hall as part of the royal burgh’s 600th anniversary celebrations. Eight years later, in August 2006, the prince returned to Bute for the 200th anniversary Bute Agricultural Society Show and unveiled a cloth of estate to King James IV at Rothesay Castle.

The title of Lord of the Isles was used during the prince’s travels around the islands off the west coast of Scotland, as in April 1999 when he opened the causeway that linked Berneray with North Uist and presented the Lord of the Isles Trophy at a shinty festival. The lordship was also noticed in the Court Circular in June 2015 when he visited distilleries on Islay, and in October 2016 when he attended the Royal National Mod on Harris, as well as in January 2019 when he witnessed the centenary service to commemorate the loss of more than 200 men when the Admiralty yacht Iolaire sank at the entrance to Stornoway harbour on the Isle of Lewis.

For many years the title of great steward of Scotland was not referred to during royal visits or in public places, although the role had been noticed in The Gazette in 1902 when the Earl of Crawford, a senior earl in the peerage of Scotland, walked in the coronation procession as “lord high steward of Scotland … as deputy to His Royal Highness the Duke of Rothesay” (Gazette issue 27489).

A similar role was assigned to the Earl of Crawford in 1911, but no appointment was made in connection with the 1937 coronation as there was no duke of Rothesay or great steward to deputise. When Queen Elizabeth was crowned in June 1953 the current holder of the earldom of Crawford, who had acted as a page to his father in 1911 (Gazette issue 40020), was named as deputy to Prince Charles as great steward.

The stewardship became more widely known during the 21st century after Prince Charles used his Scottish title to promote an interest in Dumfries House, a mansion at Cumnock in Ayrshire that formerly belonged to the marquesses of Bute. Work to preserve the house and its contents, and to regenerate the estate, was managed through an organisation that operated under the name of the Great Steward of Scotland’s Dumfries House Trust from 2007 until 2018, when it merged to form the Prince’s Foundation (which had interests in other royal properties such as Highgrove House and the Castle of Mey in Caithness).

The prince had no distinctive coat of arms or emblems that attached to any of his Scottish titles until, following a Welsh precedent, the Queen issued a royal warrant in September 1974 in which she assigned a personal banner for her son’s use in Scotland. The flag showed quarters that represented the titles of great steward of Scotland and lord of the Isles, with a central shield bearing arms for the dukedom of Rothesay, consisting of the royal lion rampant and double tressure “charged over all at the honour point with a label of three points azure”.

Prince Charles was referred to by his Scottish dignities in the last Court Circular of the late Queen’s reign, in which he was described as Duke of Rothesay when he visited the New Lanark World Heritage Site and attended a dinner at Dumfries House on 7 September 2022, which would prove to be the eve of his last journey to be with his mother at Balmoral.

About the author

Russell Malloch is a member of the Orders and Medals Research Society and an authority on British honours.

See also

The Accession of King Charles III

Succession to the Crown: An introduction

Gazette Firsts: The history of The Gazette and royal coronations

Find out more

Royal Marriages Act 1772 (Legislation)

Succession to the Crown Act 2013 (Legislation)

Coinage Act 1971 (Legislation)

Civil List Act 1952 (Legislation)

Civil List Act 1972 (Legislation)

Crown Lands Act 1702 (Legislation)

Images

The Gazette

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Publication date: 11 April 2023

Any opinion expressed in this article is that of the author and the author alone, and does not necessarily represent that of The Gazette.