Women and D-Day

To mark the 80th anniversary of the Normandy landings, Andrew Whitmarsh, Curator of The D-Day Story museum in Portsmouth, looks at the role women played in D-Day and World War 2 as a whole.

What role did women play in the Normandy landings?

Women have been involved in and deeply affected by warfare for thousands of years. However, their roles have often been overlooked when the story of those conflicts is told. Despite increased attention to the subject in recent years, this is perhaps still true for the Second World War.

Women were caught up in that conflict because it was a total war, affecting the whole of society regardless of sex, age or whether they were civilians or in the armed forces. In wartime many women took on civilian work that in the past had been thought of as suitable only for men.

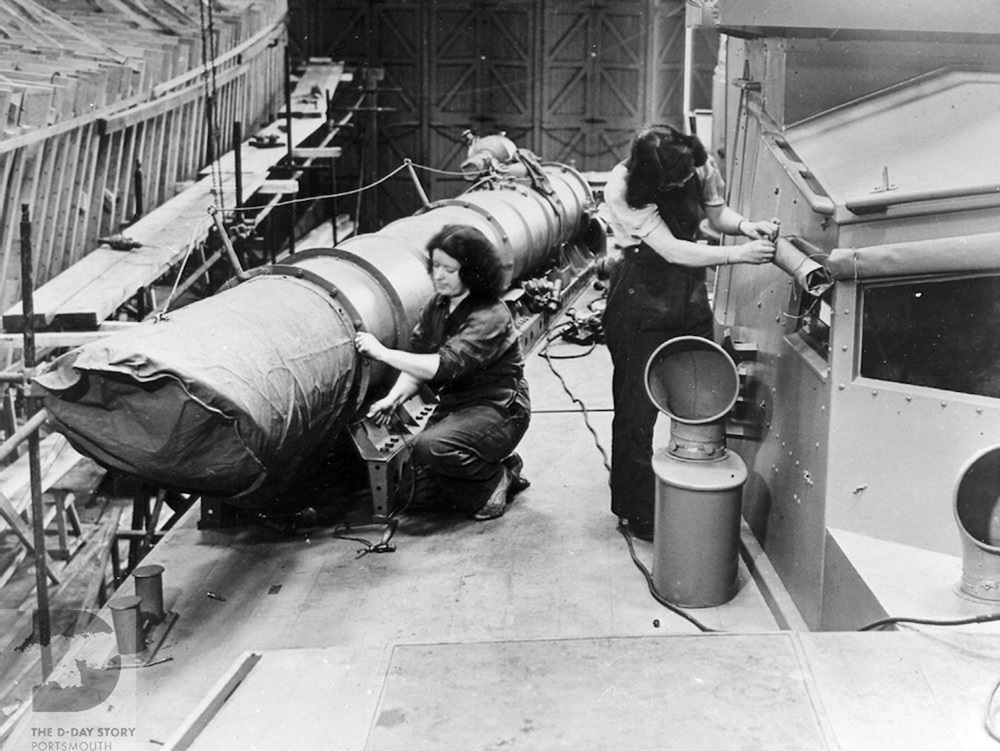

The photograph below shows two women working on a Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) that was being built by Vosper. MTBs like this one played a key role on and after D-Day as one of the outer lines of defence for the Allied fleet.

Women working on a Motor Torpedo Boat. Photograph courtesy of Vosper Thornycroft.

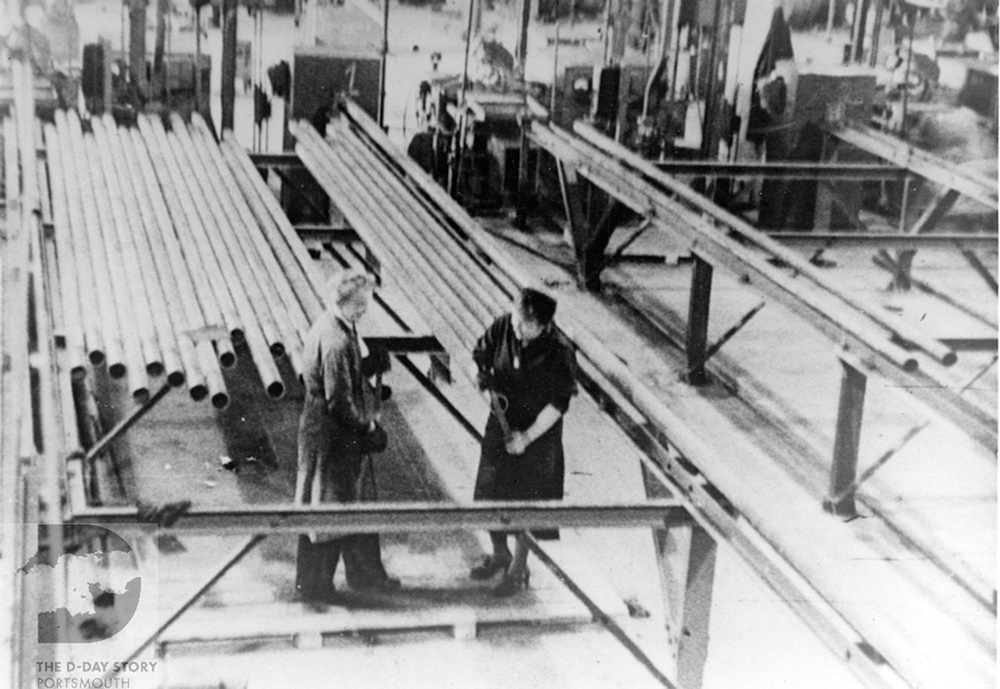

The next photograph shows two women at the BICC (British Insulated Callender’s Cables) factory, where 20ft (6m) sections of three-inch (76mm) wide PLUTO pipeline were made; some of the pipeline sections can be seen on the rack behind them. PLUTO stood for Pipe Line Under the Ocean. It was laid across the English Channel several months after D-Day, enabling fuel to be pumped across to France with minimal risk of being intercepted by enemy action.

Female workers at the BICC factory making PLUTO. Courtesy of The D-Day Story.

Some of the equipment used on D-Day was invented by women. Joan Elizabeth Strothers (Lady Curran) was a physicist who developed a means of defeating radar known as ‘chaff’ or ‘window’. This consisted of strips of metallic foil which could create false echoes on an enemy’s radar screen, disguising the presence of real aircraft.

Joan was studying for a PhD when the war intervened, and was one of many physicists who turned their skills to create new military equipment. While working in the radar countermeasures group at the Telecommunications Research Establishment, she developed the concept of disrupting enemy radar using radar reflectors.

The Allies first used ‘window’ in July 1943. On 6 June 1944 it was used as part of the Allied deception plan, in what was known as Operations Glimmer and Taxable. In the early hours of D-Day, aircraft of 218 and 617 Squadrons RAF flew across the English Channel, making repeated circuits and dropping ‘window’ at intervals. This gave the impression on enemy radar screens of a large naval fleet crossing towards northern France. The Allies hoped that this would delay German troops from being moved from that part of the country to Normandy against the troops landing there.

During the First World War (1914-1918) women had supported the war effort both in civilian work and in uniform. Building on this for the next major conflict, the British armed forces and nursing services again began recruiting women.

Nursing was traditionally thought of as a female role. Dorothy Hansell was a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse who worked at Queen Alexandra Hospital in Portsmouth at the time of D-Day. That hospital, as well as many others all along the south coast of England and further inland, treated the many wounded troops brought back from Normandy.

Left, Nurse Dorothy Hansell and colleagues with wounded soldiers who were recovering at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth. Right, Dorothy Hansell’s Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) cap. Courtesy of The D-Day Story.

Female nurses also served in Normandy, with the first arriving less than a week after D-Day. The photograph below shows a US Army nurse, 2nd Lieutenant Margaret Stanfill of the 128th Evacuation Hospital, at Boutteville in France on 14 June 1944.

US Army nurse 2nd Lieutenant Margaret Stanfill in Normandy. Photo: Conseil Régional de Basse-Normandie / US National Archives.

Many women served in the UK in support of the Normandy Landings, whether during the preparations for the landings and/or during the campaign itself. The photograph below shows Wrens (members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service) who were based at HMS Excellent, a shore base at Whale Island in Portsmouth. The Royal Navy Gunnery School was located at HMS Excellent, and preparations for the naval gunfire support of the Allied armies in Normandy were made there.

Wrens including Jean Sandford at HMS Excellent, Portsmouth, during the Second World War. Jean and some of these other Wrens operated a small boat in the Solent which seems to have been a guard ship for anti-aircraft gun practice range off the coast. Courtesy of The D-Day Story.

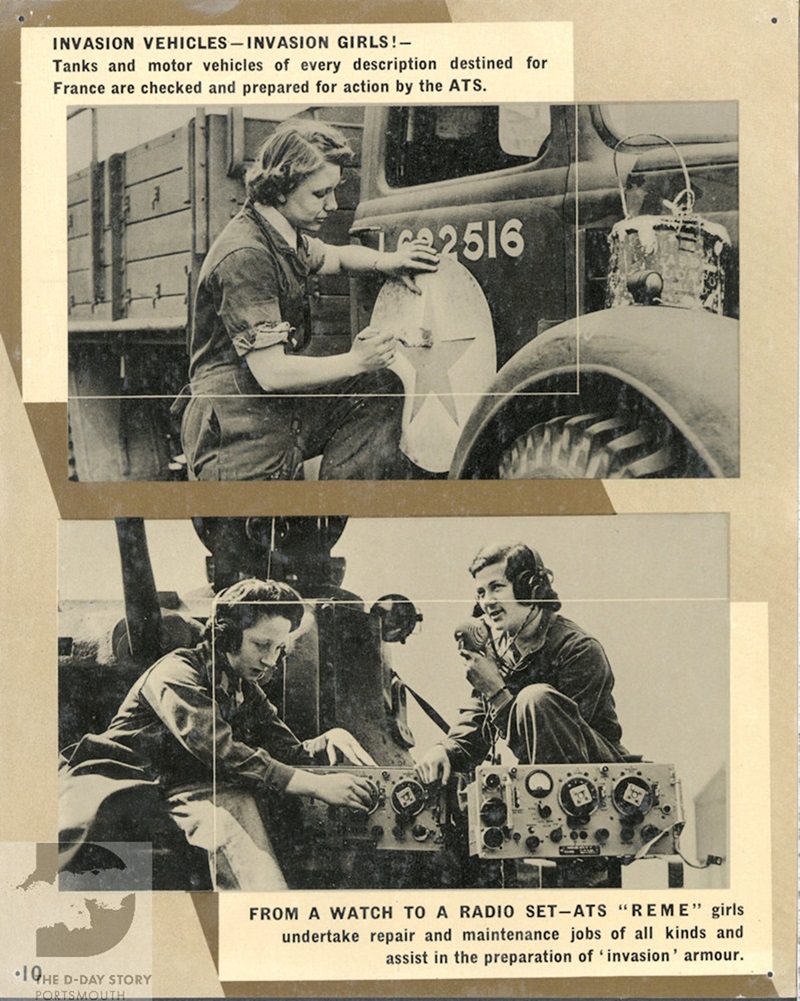

The image below shows one of a set of government information posters that were produced in around 1945, illustrating the contributions of women’s services to the war effort. The upper photograph on the poster shows a member of the ATS (Auxiliary Territorial Service: the British Army’s women’s service) painting an Allied recognition star onto the side of a lorry before D-Day. The lower image shows ATS women attached to the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) who are preparing radio equipment for use in Normandy.

This poster was one of a set produced by the Ministry of Information called “Women in Action”, showing the roles carried out by women in the British armed forces during the Second World War. Courtesy of The D-Day Story.

Civilians also supported the Allied armed forces directly in a variety of roles. The photograph below shows female and male British civilians who worked with American soldiers at Rugby Camp, Hilsea, Portsmouth, in around 1943-1944. The civilians’ role was probably helping prepare and store military equipment ahead of the landings in France.

British civilians who worked at an American Army base in Portsmouth. American soldiers can be seen in the front row. They include Michele (Mikey) Ciampanelli, who served in 49th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Brigade, US Army. After D-Day his unit landed on the continent. Courtesy of The D-Day Story.

Women also played important roles supporting the Allied cause in Nazi-occupied France. This photograph shows members of the Maquis (French Resistance group) at La Tresorerie near Boulogne on 14 September 1944. We are not sure what the story of this group is, but the woman certainly appears to be in a leadership role. The Resistance played an important role in obtaining information for the Allies, and in sabotaging the German war effort.

Members of the maquis at La Tresorerie. Photo: Libraries and Archives Canada.

Another example of a woman who played a vital role behind Nazi lines was Pearl Witherington, an agent with the British secret organisation, Special Operations Executive (SOE). She parachuted into the Loire region of France in September 1943 to act as a courier for a resistance network run by Maurice Southgate. When her male commanding officer was arrested by the Nazis, Pearl took on the leadership of the Resistance group, which eventually grew to a strength of 2,600 Resistance fighters. Her forces killed 1,000 enemy soldiers and took the surrender of 18,000 more.

After 1945 Pearl was recommended for a military honour to mark her accomplishments but as a woman was considered ineligible. She was offered the civil MBE instead, but turned it down saying: “There was nothing civil about what I did.”

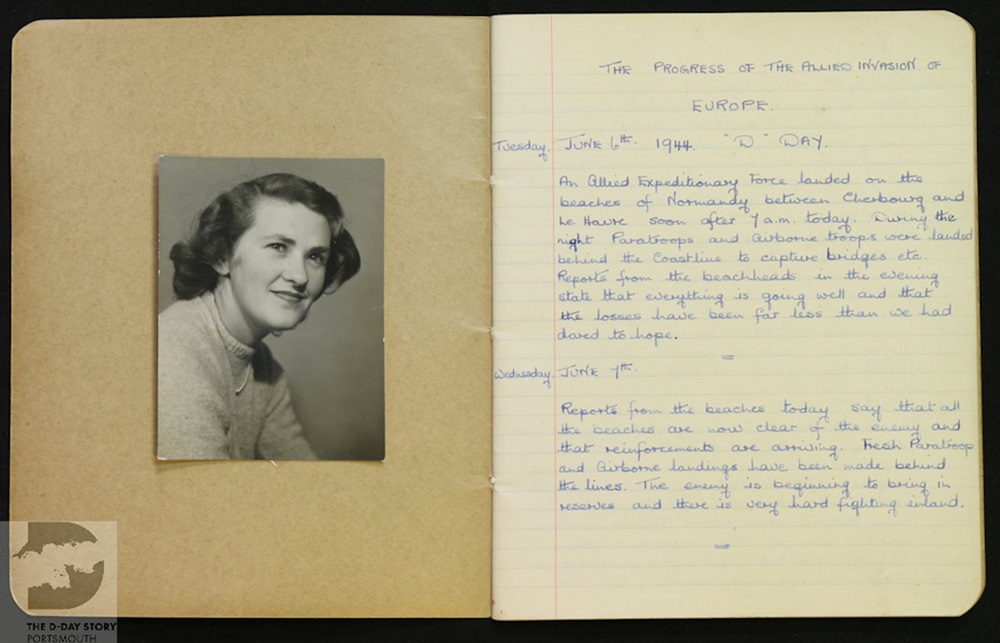

On and after D-Day, many women remained in the UK and waited anxiously for news with their male relatives serving overseas. Shirley Gann was living in Kent and kept diaries for the period 6 June 1944 to 12 January 1945. She suspected that her brother John would soon be landing in France. Each day’s diary entry is a summary of what she had seen in newspapers or heard on the radio, so she could try and understand where her brother might be. John was serving in the Royal Artillery in 49th Infantry Division, and landed in Normandy on 9 June.

Shirley Gann (whose photograph is on the left) kept these diaries recording information about the Allied forces in France, to understand where her John brother might be. Courtesy of The D-Day Story.

Amongst French civilians, women were greatly affected by the fighting as much as men. The next photograph was taken in Normandy by a US Navy photographer (possibly Lieutenant Commander Fred Gerretson USNR and men of his unit, US Combat Photographic Unit 8). It was originally captioned “Street scenes in St. Mère Eglise, France after U.S. Army troops moved in during invasion. U.S. soldier and two French refugees make each other understood despite the difference in tongues.” Have a look at the photograph first, and then read the moving story behind this image which follows after it.

A US soldier talks to two French women, in the town of Ste. Mère Eglise. Photo: US Navy.

At first glance this photograph might seem to show a casual conversation. However, a closer look at the expression on the face of the older lady in the centre hints at the more complex true story. The lady’s name was Madame Joan, and her daughter is standing next to her. Madam Joan’s husband had been accidentally killed in the fighting during the Battle of Normandy: he was killed by shellfire on 7 June 1944.

Many French civilians suffered a similar fate, as the places where they lived and worked suddenly became a battlefield. It is likely that the Joans’ home had been destroyed, and that the two women were holding the only possessions that they had been able to carry away with them when they happened to walk past the US soldier. This is perhaps a cautionary tale illustrating how it can be easy to overlook the suffering caused by war, which in the Second World War impacted women just as much as men.

This article was originally published on The D-Day Story website.

About the author

Andrew Whitmarsh is a Curator at The D-Day Story in Portsmouth, a museum which tells the story of D-Day and the Battle of Normandy. It holds over 10,000 items – preserving, researching and acquiring objects to share with the public through exhibitions, workshops and other activities.

See also

D-Day and The Gazette - 80th anniversary

D-Day 80th anniversary events UK

D-Day heroes: Major John William Guy Shearman

Publication date

21 May 2024

Any opinion expressed in this article is that of the author and the author alone, and does not necessarily represent that of The Gazette.