Demise of the Crown: #9: The three Kings

As the official public record since 1665, The Gazette has been recording the deaths of monarchs for over three centuries. As part of our ‘Demise of the Crown’ series, historian Russell Malloch looks through the archives at The Gazette’s reporting of the demise of King George III.

Three Kings

The funerals of George III in 1820, George IV in 1830 and William IV in 1837 all took place at Windsor, where each king had lived and died, and where they consumed large amounts of private and public money in trying to enhance the amenity of the estate, as well as completely altering the visual appearance of the castle.

Windsor continued to be the preferred venue for family departures, although the situation seemed to be in doubt for a time, as the Regent had transferred the Garter chapters back to London, and to his court at Carlton House, while Westminster Abbey was enjoying its other royal roles, as in hosting an installation of knights of the Bath in 1812.

The relationship between the court and the sovereign’s principal residences shifted in favour of Windsor in 1824, after the government agreed to fund a significant programme to improve the accommodation. The project transformed the built environment and increased the height of the castle’s Round Tower by more than 30 feet, so that it now stood above the roof of St George’s Chapel. The work cost more than £1 million in the money of the 1820s, and was not finished until after George IV’s death, although The Gazette reported that the King knighted Jeffry Wyatville, the architect responsible for his Windsor scheme, in 1828 (Gazette issue 18531).

The Gazette’s account of the last three Hanoverian funerals differed from the procedure for the last of the Westminster Abbey burials in 1760, when George II’s ceremonial was gazetted one week before the funeral, rather than afterwards. This meant that the report about the proceedings to lament the demise of the crown in 1820 was the first detailed narrative to appear in The Gazette.

This was also the first time The Gazette recorded both the birth and death of the sovereign, as a notice from Whitehall had explained that George III’s arrival took place on 24 May 1738 (Gazette issue 7704). That notice was gazetted before the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1752, when 11 days were added to the old Julian style of date, and so the King’s birthday was always celebrated on 4 June each year.

There were common elements to marking the passing of the last three Hanoverians, with the body being set out in one of the state apartments at Windsor Castle, and with the public being admitted to view the royal remains during two days before the service. The Audience Chamber was used for that purpose in 1820, while the Great Drawing Room was chosen in 1830 and the Waterloo Chamber in 1837. On each occasion the coffin was covered with a purple velvet pall, decorated with escutcheons of the royal arms.

The personal union of the crowns, which had existed since the creation of the kingdom of Hanover in 1814, was recognised on this occasion by placing two crowns on the coffin, one for the United Kingdom and the second for Hanover.

During the lying in state, one of the lords of the bedchamber sat at the head of the coffin, and the body was attended by the Yeomen of the Guard and Band of Gentlemen Pensioners. The late Hanoverian obsequies observed the contemporary practice of holding a night-time ritual, and so the soldiers who flanked the processional route were supplied with a flambeau or flaming torch to light the way to St George’s Chapel.

King George III

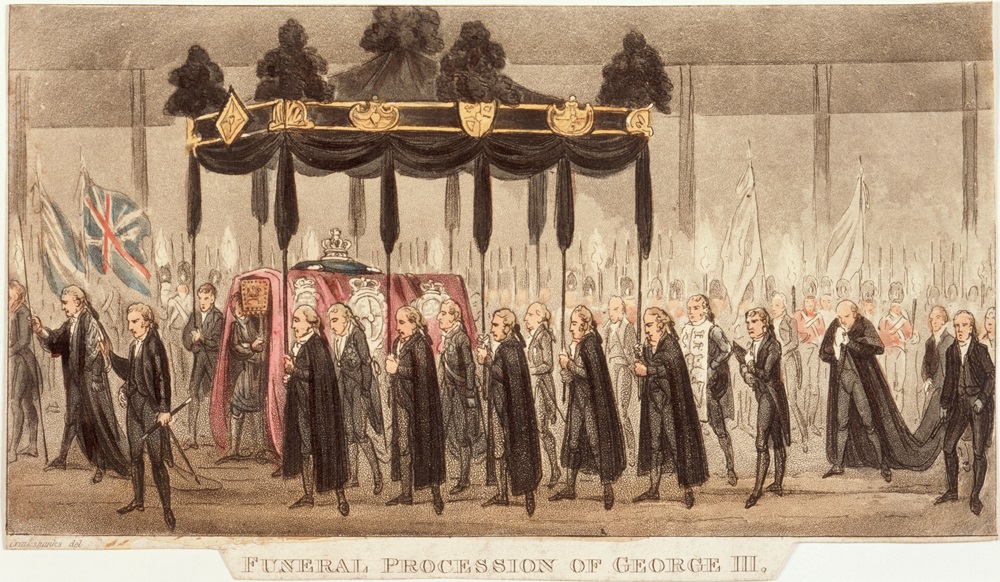

George III’s cortege in February 1820 was led by the band of the Foot Guards, and marshalled by the officers of arms, who had long experience of organising royal gatherings (Gazette issue 17567*). The procession included the Knight Marshal and his men, and the Poor Knights of Windsor, who were followed by the sovereign’s medical and ecclesiastical staff, and members of the royal households; then judges and law officers; privy counsellors; members of the House of Lords and their eldest sons, as well as bishops and the great officers of state.

The parade recalled the heraldic colours of Queen Mary’s funeral in 1695, as peers were given the job of supporting banners representing Brunswick, England, Hanover, Ireland, Scotland and the United Kingdom, as well as the royal standard. The Hanoverian crown was carried by an official from the German legation, while the imperial state crown was carried by a deputy acting for Clarenceux king of arms, the officer to whom the role was normally assigned.

The lord steward and the lord chamberlain came next, and then the royal coffin borne by ten Yeomen of the Guard. The pall bearers included the Duke of Wellington, the victor of the battle of Waterloo, while the Gentlemen Pensioners walked with their weapons reversed, just as they did in 2022. The Garter’s two secular officers, the king of arms and the usher of the Black Rod, came next, and then the chief mourner, the King’s son Frederick, Duke of York, in a long black cloak with a Garter star embroidered on the side, and wearing the collars of the Garter, Bath and Guelphic Order.

The restricted circumstances in which the King had passed his last few years were reflected in the fact that the procession ended with members of the council of the Duke of York as custos personae of his late father (including the lord chancellor, and the archbishops of Canterbury and York), along with officers from the Windsor Establishment, and the late King’s trustees.

The King’s remains and regalia were placed on a platform in St George’s Chapel, with the Duke of York taking his place at the foot of the coffin, and the lord chamberlain at the head, while the peers bearing the banners were arranged on each side of the quire below the altar. After the dean concluded the burial service, the King’s body was deposited in his crypt and Garter King of arms pronounced his style and titles. The chief officer of the Windsor Establishment, known as the groom of the stole, then broke his staff of office and deposited it in the vault.

The Gazette noted that funeral guns were fired at five minute intervals during the procession, while minute guns were fired on the proclamation of the King’s style and titles.

Most Sacred Majesty

The opening sentence of the deputy earl marshal’s report about the funeral, which appeared in The Gazette of February 1820, referred to George III as “His late Most Sacred Majesty”, rather than by the style Garter king of arms used during the committal service, which was “Most High, Most Mighty, and Most Excellent”.

The introduction of the holy prefix in this setting recalled the papal titles that were used by several European sovereigns at this period. The king of France, for example, was often referred to as Christian, while the Portuguese monarch was faithful, and the king of Spain was Catholic. Readers of the regency Gazette saw these styles being adopted by the officials who drafted the Garter’s statutes of April and August 1814 that were issued to His Most Christian Majesty Louis XVIII, King of France and Navarre (Gazette issue 16888), and His Most Catholic Majesty Ferdinand VII, King of Spain, on being made members of the order (Gazette issue 16925).

The “Most Sacred” prefix had appeared in the Stuart Gazettes, and a few of the Hanoverian editions, but it was seldom used in most formal settings in the United Kingdom. The holy designation had, however, featured in a Privy Council order in November 1818, which reflected the procedures that were implemented after the death of certain members of the royal family. In this instance, the prayer to be used by the Church of England was revised because of the death of Queen Charlotte, and the new prayer described the King as “His Most Sacred Majesty” (Gazette issue 17422).

The Gazette’s reports about the funerals of George IV (Gazette issue 18707) and William IV (Gazette issue 19519) were issued under the name of the Duke of Norfolk, who was the leading Catholic peer in England, as well as the earl marshal, and they continued to refer to the sovereign as “Most Sacred”. The same prefix was used by a later Duke of Norfolk, who subscribed the report relating to Queen Victoria’s funeral service in 1901.

The papal style of designation was generally dropped from official settings after 1901, perhaps because it was deemed unsuitable or inappropriate in parts of the royal domain. In May 1910, a few days after the demise of Edward VII, the clerk of the Privy Council (Almeric FitzRoy), was approached by the lord high commissioner to the Church of Scotland in connection with George V’s prefix, as he “thought it necessary to complain of the King’s description as “His Most Sacred Majesty” in the order exhorting the Scottish churches to alter their forms of prayer for the royal family, assuring me that it was wounding to Scottish sentiment, as appearing to deify the King after the fashion of the Roman Emperor!”. FitzRoy passed the high commissioner’s concern to the Asquith government’s secretary for Scotland, who “scouted the notion that the point had any importance”.₁

King George V and his son were still described as “sacred” in the earl marshal’s orders relating to the robes and dress to be worn at the coronations of 1911 and 1937, while Elizabeth II was described in the Duke of Norfolk’s coronation order of December 1952 as being “Her Most Sacred Majesty” (Gazette issue 39709).

*Issue is currently not available on The Gazette website. See more details.

Succession to the Crown: From Charles II to Charles III

Succession to the Crown is essential reading for anyone with a keen interest in the British royal family and provides an excellent and trusted source of information for historians, researchers and academics alike. The book takes you on a journey exploring the coronations, honours and emblems of the British monarchy, from the demise of King Charles II in 1685, through to the accession of King Charles III, as recorded in The London Gazette.

Historian Russell Malloch tells the story of the Crown through trusted, factual information found in the UK's official public record. Learn about the traditions and ceremony engrained in successions right up to the demise of Queen Elizabeth II and the resulting proclamation and accession of King Charles III.

Available to order now from the TSO Shop.

About the author

Russell Malloch is a member of the Orders and Medals Research Society and an authority on British honours. He authored Succession to the Crown: From Charles II to Charles III, which explores the coronations, honours and emblems of the British monarchy.

See also

King Charles III and The Gazette

Gazette Firsts: The history of The Gazette and monarch funerals

Find out more

Succession to the Crown: - From Charles II to Charles III (TSO shop)

References

- Sir Almeric FitzRoy, Memoirs, Volume II, page 406.

Images

The Gazette

Immanuel Giel

Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

The Gazette

Publication date

2 December 2024

Any opinion expressed in this article is that of the author and the author alone, and does not necessarily represent that of The Gazette.