Demise of the Crown: #22: Sandringham to St George's (Part II)

As the official public record since 1665, The Gazette has been recording the deaths of monarchs for over three centuries. As part of our ‘Demise of the Crown’ series, historian Russell Malloch looks through the archives at The Gazette’s reporting of demise events following the death of King George V.

George V demise

King George V died at Sandringham House just before midnight on 20 January 1936 (Gazette issue 34244), and the Court Circular reported that “During the last moments of His Majesty the archbishop of Canterbury read special prayers and conducted a short service in the King’s room”, and on the evening of the following day his coffin was taken to the local church in Norfolk where a private service was held.

Cosmo Lang, the archbishop of Canterbury, reported the first change to be made by Edward VIII: “After midnight he ordered all the clocks, which by long custom at Sandringham were kept half an hour in advance of the real time, to be put back! I wonder what other customs will be put back also!”₁

There were early changes to other recent practices, as with restricting the duration of the mourning for the late sovereign. The period had been set at one year after the loss of Queen Victoria, and was reduced after Edward VII’s demise, for business rather than family reasons. The subject remained in the hands of the Duke of Norfolk, as the earl marshal and hereditary marshal of England, rather than a person with a remit that extended across the whole of the United Kingdom.

The Gazette of January 1936 set out the new scheme, which limited the mourning period to just one week. The earl marshal stated that “it is expected that all persons upon the present occasion of the death of His late Majesty of blessed and glorious memory do put themselves into mourning to begin on Wednesday the 22nd of this instant, such mourning to continue until after His late Majesty’s funeral”, which took place on 28 January.

The general mourning provisions from 1936 were adopted after the death of George VI in 1952, and in a modified form after the demise of Elizabeth II in 2022, and so they only applied for a week or so, from the demise of the crown, until after the funeral. Separate rules were made for the period of court or royal mourning, which usually only applied to family members and their households.

Accession Council

On the day of the Sandringham service, the new sovereign travelled to London to attend his accession council, when the official document that was signed by the archbishop of Canterbury, the prime minister, the earl marshal and many other counsellors who were present at St James’s Palace on that occasion, stated that the royal death “has caused one universal feeling of regret and sorrow to His late Majesty’s subjects, to whom he was endeared by the deep interest in their welfare which he invariably manifested, as well as by the eminent and impressive virtues which illustrated and adorned his character” (Gazette issue 34245).

Edward VIII had to deal with his father’s legacy, and in his memoir the Duke of Windsor wrote:

“I called a meeting of a committee of the civil and military officials responsible for the ceremonial. The funeral of a sovereign inevitably requires a vast public show – a display of state pomp and circumstances that inescapably runs counter to the bereaved family’s desire for privacy and simplicity. My mother shrank from a repetition of the prolonged manifestations of grief that marked the obsequies of my grandfather. Her one request to me before I left Sandringham was that my father should not remain unburied for more than a week. When I conveyed her wish to the committee, they readily offered to comply.”₂

The King ordered a bearer party from the Grenadier Guards to be sent to Norfolk:

“When I returned to Sandringham on the Wednesday afternoon, it was to find that my father had been placed in a coffin made from an oak-tree felled on the estate, and, escorted by the Guardsman from the Big House, taken to the little church nearby. I went there directly. The coffin rested before the altar, watched over by gamekeepers, gardeners, and other faithful retainers, who in this way were able to pay a last tribute not only to their King but to a beloved squire. As I stood there, it came to my mind that my father would have preferred that his earthly remains be spared the huge state funeral and buried in the peaceful churchyard at Sandringham. But Windsor claims the bodies of British monarchs […]”.

Windsor did claim the monarch’s body in 1936, and The Gazette explained how the King’s remains moved from St Mary Magdalene at Sandringham to Wolferton Station. Then from Wolferton to King’s Cross, and King’s Cross to the centre of London, for the public lying in state, followed by the main procession from Westminster Hall to Paddington Station. Finally, the journey from Paddington, and the procession through Windsor to St George’s Chapel.

Norfolk to London

The Duke of Windsor described the scene as he and his brothers walked to Wolferton, behind a gun carriage drawn by six horses, and with the casket covered by a royal standard, a white cross of flowers from Queen Mary, and a wreath of red and white carnations from the King and his siblings:

“Then came a groom leading my father’s white shooting pony, Jock. Bringing up the rear of the simple procession were some hundreds of plainly dressed men and women, tenants and workers on the estate, neighbours, friends, and gamekeepers in green liveries and black bowler hats. With them marched the old piper, Forsyth, playing “The Flowers of the Forest.” … Just as we topped the last hill above the station, the stillness of the morning was broken by a wild familiar sound – the crow of a cock pheasant. My brothers and I glanced up in time to see a solitary bird flying across the road directly overhead. In the symbolism of that felicitous incident our sadness momentarily disappeared. The thought occurred to all of us that had my father been vouchsafed the choice of one last sight at Sandringham he would have chosen something like that: a pheasant travelling high and fast on the wind, the kind of shot he loved.”

The imperial state crown had been placed on the coffin by the time it reached King’s Cross, where the bearer party of the Grenadier Guards transferred it to a gun carriage drawn by the Royal Horse Artillery, which brought the king’s body to Westminster Hall to lie in state for four days. Just a few months earlier the hall was the setting for a meeting of both Houses of Parliament, when the speaker of the Commons and the lord chancellor had offered their congratulations to the King on completing 25 years of his reign.

Maltese Cross

Another change to recent precedent was suggested by Edward VIII, as Archbishop Lang of Canterbury wrote about the lying in state:

“On Tuesday the King had said to me that he did not wish any religious service to be held, as – said he – he was anxious to spare the Queen. But I insisted that, however short, there must be some such service. Certainly the whole ceremony would have been, as it were, blank without it; and it was at the Queen’s own wish that the one hymn – “Praise my soul, the king of heaven” – was to be sung. I borrowed from Westminster the purple cope used at the funeral of Charles II. […] I have been present at many great ceremonies, but I cannot remember any more impressive.”

Having accepted the archbishop’s advice, Edward VIII, along with his brothers, brother-in-law (the Earl of Harewood), and only 16 members of the royal household, walked behind the coffin, as it was carried past the Cenotaph in Whitehall, towards its religious reception in Westminster Hall. An ominous event occurred, which was noticed by the press, and referred to in Edward’s memoir:

“That simple family procession through London was, perhaps, more impressive than the state cortège on the day of the funeral, and I especially remember a curious incident that happened on the way and was seen by very few. The imperial crown, heavily encrusted with precious stones, had been removed from its glass case in the Tower and secured to the lid of the coffin over the folds of the royal standard. In spite of the rubber-tired wheels, the jolting of the heavy vehicle must have caused the Maltese cross on the top of the crown … to fall. For suddenly, out of the corner of my eye, I caught a flash of light dancing along the pavement.

My natural instinct was to bend down and retrieve the jewels, lest the equivalent of a king’s ransom be lost for ever. Then a sense of dignity restrained me, and I resolutely marched on. Fortunately, the company sergeant-major bringing up the rear of the two files of Grenadiers flanking the gun-carriage had also seen the accident. Quick as a flash, with scarcely a missed step, he bent down, scooped up the cross with his hand, and dropped it into his pocket. […] It seemed a strange thing to happen; and, although not superstitious, I wondered whether it was a bad omen.”

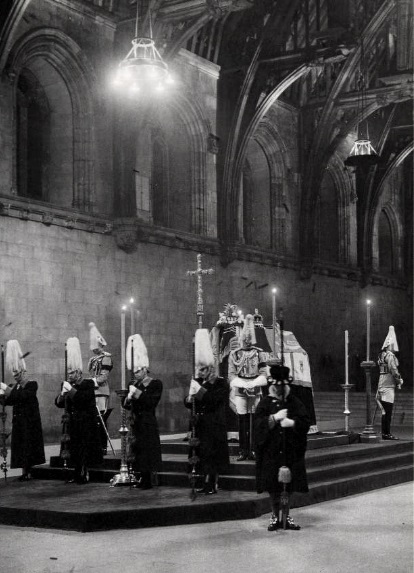

The Westminster Hall procedure was similar to 1910, as the casket was received by the archbishop of Canterbury, the earl marshal, the lord great chamberlain, the first commissioner of works, and the dean of Westminster. It was borne into the hall by a bearer party of the King’s Company, Grenadier Guards, and set on a catafalque, while an orb and sceptre joined the imperial crown. After a short service, four Guards officers stood duty, as four candles burned at the corners of the raised platform, and they were helped by the Gentlemen at Arms and Yeomen of the Guard.

The catafalque was covered by the Actors’ pall that was used for the Unknown Warrior in the abbey in 1920, and for Queen Alexandra in 1925 but, as was mentioned earlier, not for the lying in state of George VI in 1952 or Elizabeth II in 2022.

The King reflected on the state dinner he gave at Buckingham Palace on the eve of his father’s funeral, and noted that “Such feasting and commingling, with my father still unburied seemed to me unfitting and heartless. Yet there was no escaping the duty. When finally the last guest had departed, my three brothers and I slipped quietly away to carry out a plan upon which we had decided in the afternoon.” That plan was to pay their respects “in a simple and wholly appropriate way”, by changing into full-dress uniform and stationing themselves around the catafalque, between the officers who were already on vigil:

“Even at so late an hour the river of people still flowed past the coffin. But I doubt whether many recognized the King’s four sons among the motionless uniformed figures bent over swords reversed. We stood there for twenty minutes in the dim candlelight and the great silence. I felt close to my father and all that he had stood for.”

Edward decided that, as his father had been a sailor, “he should have a sailor’s funeral” and so the Royal Navy pulled the gun carriage to Paddington, rather than use horses in London and then the services of a naval unit at Windsor, as had happened by accident in 1901, and by design in 1910. The 1936 procession also took place on foot, rather than on horseback as it had done for Victoria and Edward VII.

As with the 1910 funeral, the officers of arms did not join the London cavalcade, although there was a small civil contingent from the police and fire services, but only as part of what was otherwise an event that reflected the sovereign’s role as head of the armed forces.

The state procession was attended by family members, along with the kings of Bulgaria, Denmark, Norway and Romania, the president of France, and other foreign representatives. One well-known figure in the Spanish delegation was General Franco, who attended the funeral just months before the start of the civil war that brought him to power. The crowds in London were unexpectedly large and difficult to control, and so the train was 40 minutes late in reaching Windsor.

The Gazette recorded a change to the ritual at the close of the service, after the King had placed the King’s Company colour of the Grenadier Guards on the casket. The master of the household had the honour of casting earth on the coffins of Victoria and Edward VII, but it was decided that this personal act of respect should be performed by the sovereign. And so, Sir Derek Keppel, who had served as master of the household since 1913 (Gazette issue 28678), passed a silver casket containing earth from the burial ground at Frogmore to the King, which he then cast on his father’s coffin.

Funeral honours

Edward VIII followed his father and grandfather in using the Royal Victorian Order and its medal to reward the men who helped with the funeral and, in line with the disclosure policy at this period, The Gazette reported the appointments to the order (Gazette issue 34253), but not the awards of the Royal Victorian Medal.

The first general investiture of Edward VIII’s reign was held at Buckingham Palace on 18 February 1936, when the King presented the Victorian Medal to the men of HMS Excellent, and the Gunnery School at the Royal Naval Barracks at Chatham (HMS Pembroke), who drew the gun carriage, and to personnel from the Life Guards, Royal Horse Guards, Royal Horse Artillery and Grenadier Guards, who performed special duties at Sandringham, London and Windsor. The recipients included Captain Arthur Power of the Royal Navy, who received the CVO from Edward in 1936, and took part in George VI’s obsequies in 1952, by which time he held high command, and had risen to the rank of admiral of the fleet.

St George’s Chapel

One event that usually followed a demise of the crown, was the presentation of addresses to the new sovereign by local and national organisations, in which they lamented the passing of the late monarch and welcomed the accession of their successor.

The Gazette had published such addresses for more than two centuries by the time it reported the words of the dean and canons of St George’s Chapel, which were presented to Edward VIII at Windsor Castle by Albert Baillie, the dean who composed the statement about ‘the Rule of 1928’ which had revised the royal family’s burial practices.

In the address, the dean and canons offered their condolences on the death of the late sovereign, and referred to the King’s presence “in your Garter stall on an early day in your reign”, which “assured us anew of your own high regard for the shrine in which your Majesty’s predecessors have joined with your college in the worship of almighty God.” The King replied (Gazette issue 34280):

“My father was always keenly interested in St George’s Chapel, and its successful restoration was, I know, a source of great happiness to him. […]

For my part, I have a deep affection for the chapel with its historical associations with my family and with the Order of the Garter, the pre-eminent order of chivalry of which I am now the sovereign head and you may rely upon my abiding interest in all that concerns your ancient foundation.”

Archbishop Lang had doubts as to Edward’s commitment to his religious inheritance, and recorded a long talk he had with the King one week after the funeral:

“He said, naively, that he understood he had now to appoint bishops, and asked me to tell him, how it was done! I tried to enlighten him. He spoke of one or two clerics whom he had met; but even of these his knowledge was very faint. It was clear that he knows little, and, I fear, cares little, about the church and its affairs.”

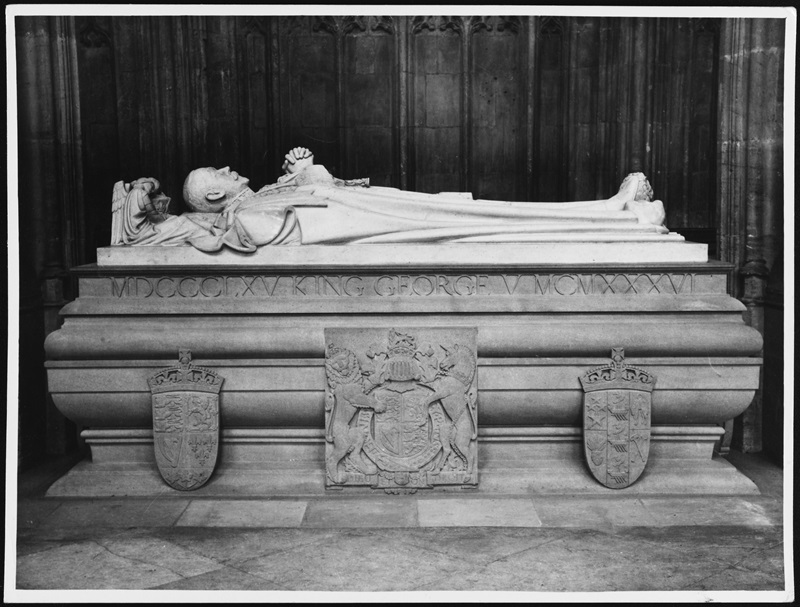

Among the men who knew about the church and its affairs, were Dean Baillie and his colleagues at Windsor, who kept a watchful eye over George V’s body after it was placed in the royal vault below the Albert Memorial Chapel, where it remained until 1939, when it was interred in a tomb in the north nave of St George’s Chapel.

The sarcophagus was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, while the recumbent figure in Garter robes on the top was by Sir William Dick, who executed several royal commissions, including images of the sovereign that were placed at Crathie, Sandringham and Windsor, and whose efforts were noticed with the dignity of knight commander in the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO) (Gazette issue 34119). The tomb was dedicated in March 1939, at a service attended by George VI and his mother.

A similar style of tomb for George V’s widow was placed beside his, in the north nave of St George’s, and showed Queen Mary in her Garter robes. The connection between the Order of the Garter and the deceased was emphasised shortly afterwards, as the banners of George and Mary that had hung in the quire after they joined in order, in 1884 and 1910, were later displayed above their effigies.

The Garter also featured in the design of one of the most prominent public monuments to the King. The statue was paid for by subscribers to a national memorial fund, which was initiated by the lord mayor of London in 1936, and supported two schemes. The first was to create playing fields for young people, while the second was to erect a statue opposite the Houses of Parliament. The sculpture was another work by Sir William Dick, and showed the King in his Garter mantle, standing on a plinth and in a setting created by Giles Gilbert Scott. The completion ceremony was delayed by the war, and so the statue was not unveiled by King George VI until October 1947.

William Dick also helped to create works to commemorate George V’s connection with the royal residences at Balmoral and Sandringham, as well as to acknowledge the personal links his family had established more recently at St Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh. These measures began in August 1938, when the King attended a service to dedicate Dick’s bust of his father, wearing the robes of the Order of the Thistle, in the small church at Crathie, which replaced an earlier kirk that stood near the entrance to the Balmoral estate, and was later demolished. Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone for the new building, and attended its dedication in 1895, and Crathie provided the setting for the first religious service to mark the passing of Queen Elizabeth II in 2022.

A plaque showing an informal portrait of George V by Dick was placed in St Mary Magdalene Church in Sandringham, and was dedicated on Christmas Day 1938, while a third memorial took a different form, as it was decided to alter the furnishings of the chapel the late King opened in 1911 to provide a spiritual home for the knights of the Thistle in Edinburgh, where they could erect heraldic plates, but all on a more modest scale than in the Garter’s chapel at Windsor.

The Thistle Chapel in St Giles’ Cathedral contained a seat that was intended to be used for investing knights, but it was removed to make way for the George V memorial, which consisted of a communion table and fittings. The table was ready by 1939, but the war intervened, and the dedication was not carried out until July 1943, when the King visited Edinburgh, where the chapel contained the stall plate that recorded his admission to the order in 1923 (Gazette issue 32819), when he married Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon.

The Edinburgh cathedral was not part of the usual royal circuit during George V’s reign, but it provided the setting for the installation of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon as the first lady of the Order of the Thistle in the summer of 1937 (Gazette issue 34396), and it would play an unprecedented part in the story of the demise of the crown in 2022.

Succession to the Crown: From Charles II to Charles III

Succession to the Crown is essential reading for anyone with a keen interest in the British royal family and provides an excellent and trusted source of information for historians, researchers and academics alike. The book takes you on a journey exploring the coronations, honours and emblems of the British monarchy, from the demise of King Charles II in 1685, through to the accession of King Charles III, as recorded in The London Gazette.

Historian Russell Malloch tells the story of the Crown through trusted, factual information found in the UK's official public record. Learn about the traditions and ceremony engrained in successions right up to the demise of Queen Elizabeth II and the resulting proclamation and accession of King Charles III.

Available to order now from the TSO Shop.

About the author

Russell Malloch is a member of the Orders and Medals Research Society and an authority on British honours. He authored Succession to the Crown: From Charles II to Charles III, which explores the coronations, honours and emblems of the British monarchy.

See also

King Charles III and The Gazette

Gazette Firsts: The history of The Gazette and monarch funerals

Find out more

Succession to the Crown: - From Charles II to Charles III (TSO shop)

Images

The Gazette

The House of Windsor

Trinity Mirror / Mirrorpix / Alamy Stock Photo

Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

The Gazette

References

- J. G. Lockhart, “Cosmo Gordon Lang” (1949), page 392.

- Duke of Windsor (1998) A King’s Story. New edition, Prion Books Ltd. Page 265.

Publication date

10 March 2025

Any opinion expressed in this article is that of the author and the author alone, and does not necessarily represent that of The Gazette.