100 years of the Order of the Companions of Honour

How conspicuous service of national importance has been recognised since August 1917.

The Order of the Companions of Honour was instituted at the same time as the Order of the British Empire in June 1917, as part of the coalition government’s scheme to reward services rendered during World War 1.

War service

The Order of the British Empire was designed to cater for a wide audience, honour activity ranging from the local to the national scale, and have an unlimited number of members. By contrast, the Companions of Honour was limited to only 50 places, and recognised ‘conspicuous service of national importance’.

Members of the order (CH) were placed immediately after the first class of the British Empire (GBE), so ranked before members of the second or knight commander class of the other orders, including the Bath (KCB). The absence of a title at this senior level in the hierarchy of honours had only one relevant precedent, which arose in the Order of Merit, an award that was highly regarded, but brought no prefix for its members.

The first CH appointments were published in The London Gazette in August 1917 (Gazette issue 30250), after the initial British Empire nominations, and reflected a variety of war-related activities, including recruiting and munitions production. The list was headed by Jan Smuts, the South African general and member of the War Cabinet, while the first British recipient was Henry Gosling of the Transport Workers’ Federation, one of a number of union leaders to be noticed for their contribution to industrial relations.

Only 17 members joined at the outset, including four women who held senior positions in the National Service Department, the Officers’ Families’ Fund and the Territorial Force Nursing Association.

The official notice about the creation of the order, together with a copy of the original statutes, was not gazetted until February 1918 (Gazette issue 30544), and the first investiture was delayed until 17 December 1918, when the King presented the insignia to General Smuts and 18 other members.

The honour was not widely used at first, with only six more nominations being made before the armistice. The order was not split into civil and military divisions, as had happened with the British Empire towards the end of 1918, nor were any grants included in the main victory honours lists, in contrast to the significant British Empire intake. A sharp difference arose in the extent of the two orders by the end of 1920, as the British Empire had more than 20,000 members, while the Companions of Honour had fewer than 30.

The order survived its wartime role and during the remainder of King George V’s reign, successive governments continued to use the CH to mark a variety of services, while few structural changes were made. The first development came in 1919, when the statutes allowed for honorary appointments, and in 1943 the maximum number of members was increased from 50 to 65, and provision was made for nominations by overseas governments. No major alterations have taken place since then, and the order still fulfils its original objective of rewarding conspicuous service of national importance.

Membership

More than 220 appointments were made between the start of the present reign in 1952 and the Birthday honours list of 2017 (Gazette issue 61962), which was published two weeks after the order celebrated its centenary. The pattern of awards from the 1930s and 40s established the basic formula that was used by later governments, as nominations were generally made for work that fell into a handful of categories, including politics, the arts, science, learning and public service.

Politics

Politics has provided the largest group of members. The honour was granted to several members of parliament for labour and recruitment work at the outset, and a few awards followed soon afterwards. Winston Churchill was admitted to the order in 1922 at the end of David Lloyd George’s premiership (Gazette issue 32766), and the political dimension grew during King George VI’s reign with the nomination of Nancy Astor, the first woman to sit in the House of Commons, and wartime grants to the first lord of the Admiralty, Albert Alexander, and the minister of War Transport, Lord Leathers.

Three British prime ministers have worn the CH badge. Winston Churchill was joined in 1945 by his deputy Clement Attlee (Gazette issue 37116), and John Major was honoured in 1998 for services to peace in Northern Ireland. The CH often featured in prime ministers’ resignation lists, marked periods in senior posts or provided compensation for loss of office, as in the case of George Osborne, the former chancellor of the exchequer.

Arts

The arts category encompasses areas that range from literature, music and the theatre, to ballet, painting and sculpture.

The first literary member was the author Sir Henry Newbolt, who joined in 1922 (Gazette issue 32563). Later recipients include well-known writers such as John Buchan, E M Forster and Graham Greene, together with more recent nominees Doris Lessing, Harold Pinter and J K Rowling.

The musical nominations cover composers, conductors and performers. Frederick Delius became the first musical CH in 1929 (Gazette issue 33472), and he was joined by distinguished colleagues such as Thomas Beecham, Benjamin Britten and Michael Tippett. The present members include the composer Harrison Birtwistle, the percussionist Evelyn Glennie and the musician Paul McCartney.

The performing arts were noticed from the 1920s when the order welcomed Lillian Baylis, the manager of the Old Vic Theatre (Gazette issue 33472), and several actors have been honoured, including John Gielgud and Alec Guinness, while the names of Judi Dench, Ian McKellen and Maggie Smith now appear on the roll.

Ballet had two outstanding representatives, Frederick Ashton and Ninette de Valois, and the visual arts were occasionally noticed with the CH, including awards to the sculptors Henry Moore and Elisabeth Frink, the potter Bernard Leach and painters such as Lucian Freud and David Hockney.

Science

The earliest scientific CH was John Haldane, who was honoured in the 1920s for work in connection with industrial diseases (Gazette issue 33390). Since then, the order has admitted several notable scientists, including the first nominee of King George VI’s reign, Charles Wilson, whose pioneering work in atomic physics gained the Nobel Prize.

Other CH laureates include Lawrence Bragg, who earned his Nobel prize for research into x-ray crystallography, and James Chadwick, who confirmed the existence of the neutron. Physiology or medicine prizes were granted to the molecular biologist Sydney Brenner, the zoologist Peter Medawar, and the biochemist Rodney Porter. Two members – Max Perutz and Frederick Sanger, both from the Medical Research Council’s laboratory of molecular biology – were awarded the chemistry prize.

In addition to the Nobel winners, the order has welcomed various prominent members of the scientific community, including current holders of the CH, such as the naturalist David Attenborough, the physicist Stephen Hawking and the environmentalist James Lovelock.

Learning

The scholarly contingent is based on a variety of disciplines and institutions, with members mainly drawn from the universities of Cambridge, London and Oxford, although the group began in the 1920s with Sir Henry Jones who held the chair of philosophy at Glasgow (Gazette issue 32563).

The present reign has witnessed learned CHs ranging from the Byzantine scholar Steven Runciman and the historian Arnold Toynbee, to the archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler. Today’s membership includes the philosopher Onora O’Neill, the economist Nicholas Stern and the art historian Roy Strong.

Public service

The public service element began in 1921, with John Clifford of the Baptist World Alliance, and he was followed by several faith and welfare leaders, including Bramwell Booth of the Salvation Army and Chad Varah of the Samaritans.

The early use of the CH for union officials was revived in the 1940s, with the appointment of George Gibson, the general secretary of the Confederation of Health Service Employees, and he was followed by employees’ leaders, including Jack Jones of the Transport and General Workers Union.

Other activities

The fields of endeavour that governments of all political parties have deemed worthy of recognising with the CH have broadened during the present reign and now include such varied occupations as architect (Richard Rogers), cook (Delia Smith), designer (Terence Conran) and sportsperson (Roger Bannister).

Overseas

Only a few overseas candidates were selected during King George V’s reign, with General Smuts of South Africa being joined by the Australian prime minister Stanley Bruce, when the nation’s new capital at Canberra was inaugurated (Gazette issue 33292), and by V S Srinivasa Sastri, the Indian government’s first agent in South Africa. Bruce was one in a small series of Australian CHs, including prime ministers Robert Menzies and Malcolm Fraser.

King George VI welcomed members from Canada, New Zealand and Rhodesia. The North American appointments were influenced by Canada’s rejection of titles, as the CH did not oblige recipients to use the prefix 'Sir' and provided an honour for senior officers who were unable to accept, say, a KCB. The CH was therefore used to mark the distinguished work of generals Henry Crerar (Gazette issue 37161) and Andrew McNaughton (Gazette issue 37607) during World War 2, while later nominees include the Canadian prime ministers John Diefenbaker and Pierre Trudeau.

The New Zealand dimension began with prime minister Peter Fraser at the end of the war, while later recipients include some of Fraser’s successors such as Robert Muldoon and David Lange.

The geographical range widened further during the present reign, but it was limited to single Commonwealth appointments for Ceylon, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea and Trinidad and Tobago. In each case the honour was conferred on the nation’s prime minister, including Michael Somare of Papua New Guinea who was admitted in 1978, and was the senior or longest serving member by the time the order reached its centenary in 2017.

The CH was not conferred on an honorary basis until 1954, when the Queen presented the insignia to Rene Massigli when he retired as the French ambassador to London. Fewer than a dozen honorary awards have followed, including Desmond Tutu, who received his badge from Prince Henry of Wales in South Africa in 2015.

The Order

The members’ insignia consists of a crowned badge. The obverse shows a knight on horseback standing beside an oak tree, from which is suspended a shield bearing the royal arms, all within a blue oval containing the motto, 'In action faithful and in honour clear', with the Queen’s cypher, E II R, on the reverse. The badge is worn from a riband described as 'carmine ... with a bordure interlaced gold'.

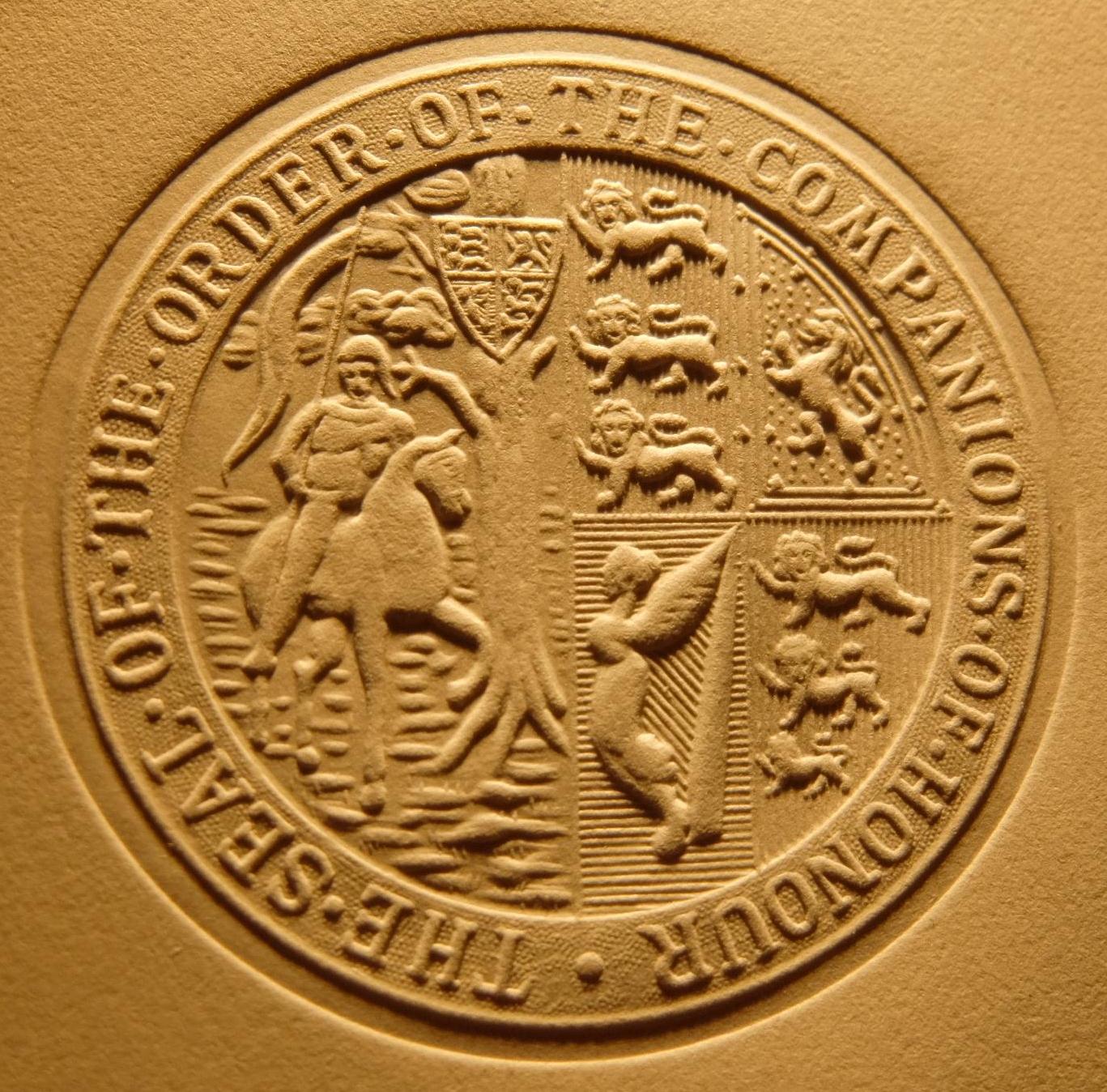

Most awards are notified in The London Gazette, and the presentation of insignia is usually reported in the Court Circular. The members’ warrants of appointment are normally signed by the Queen and the secretary and registrar of the order (the secretary of the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood), and impressed with a seal which combines the knight on horseback design with the royal arms, all within a circle inscribed 'The Seal of the Order of the Companions of Honour'.

The order has no chapel and holds no events of the kind found in many of the other orders, such as the annual Garter service at Windsor. The centenary was, however, marked by an evensong in the Chapel Royal at Hampton Court Palace in London and by a reception for members of the order, which the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh attended on 13 June 2017.

The high standing of the Order of the Companions of Honour was recognised by the Queen who, writing about the membership of the order her grandfather instituted in 1917, concluded that the 'sum total of their lives constitutes an impressive array of eminent achievement in the life of this nation and in the Commonwealth'.

About the author

Russell Malloch is a member of the Orders and Medals Research Society and an authority on British honours.