The Order of The Bath: Prime ministerial K.C.B.s

The Order of the Bath is one of the senior state honours in the United Kingdom, and one of those orders where the right to nominate members usually lies in the gift of the government, rather than the sovereign.

The Gazette recently reported the appointment of three new members to what is known as the second class, or the grade of knight commander, in the civil division of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath (Gazette issue 64480). As such, they have the right to use the prefix “Sir” and to place the letters “K.C.B.” after their name.

The three recipients of the KCB were all senior members of the government that was, until the summer of 2024, led by prime minister Rishi Sunak. The Order of the Bath then forged a close link with his successor, as the Court Circular reported that at Buckingham Palace, on 5 July 2024, the Right Honourable Sir Keir Starmer accepted the King’s offer to form a new administration, and kissed hands upon his appointment as prime minister and first lord of the Treasury. In doing so, he became the fourth prime minister to enter 10 Downing Street while a member of the Order of the Bath, as Sir Keir was also a KCB.

Russell Malloch, member of the Orders and Medals Research Society, examines the role and use of the civil knighthood of the Bath since it was established in 1847, and identifies a number of interesting recipients, as well as drawing attention to prime ministerial links with the order.

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath

The order was created during the premiership of Sir Robert Walpole (Gazette issue 6376) and will mark its 300th anniversary in May 2025. It began with a single class of member, known as knights (KB). In 1815 the membership was split into three classes, styled knight grand cross (GCB), knight commander (KCB) and companion (CB), with different insignia for the civil and military members (Gazette issue 16972). Under this Regency regime the civil awards were limited to the grand cross grade.

The order’s current structure was introduced in 1847 (Gazette issue 20737), when separate military and civil sub-divisions were created, and civil awards were extended to all three classes. Women did not join the Bath until the 1960s, when they were styled dame grand cross (GCB), dame commander (DCB) and companion (CB).

The number of places in each class and division was limited by statute. The original civil division of 1847 had a maximum of 275 members, consisting of 25 GCBs, 50 KCBs and 200 CBs. These figures increased over time, and by the start of Elizabeth II’s reign in 1952 the civil contingent stood at 486 members (27 GCBs, 113 KCBs and 346 CBs).

Nomination for membership was determined by the prime minister and/or one of the principal secretaries of state, and was restricted to individuals who had merited favour by their “personal services to the Crown” or “the performance of public duties.” Provision was made for additional and honorary awards in certain circumstances, and admission to the first and second classes allowed men and women who did not already enjoy that right, such as Keir Starmer, to assume the prefix “Sir” or “Dame”.

Public service

Keir Starmer was nominated as a civil KCB for his services as director of public prosecutions, the person within the Crown Prosecution Service who is appointed by the attorney-general, and has the duty to, amongst other things, institute and conduct criminal proceedings. He was gazetted as a member of the Bath in the New Year honours list of 2014 (Gazette issue 60728), having featured in The Gazette in 2002 when he was made a Queen’s Counsel (Gazette issue 56538), and again in 2015 when he was elected as the member of Parliament for Holborn and St Pancras (Gazette issue 61230).

Sir Keir is the fourth prime minister to have joined the Bath, and followed the Duke of Wellington, Lord Palmerston and Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman. The last prime minister to wear the order’s insignia was the Liberal leader Campbell-Bannerman, who resigned on medical advice in 1908, and was succeeded by Herbert Asquith, who was obliged to travel to Edward VII’s holiday hotel in the south of France for his first formal audience as prime minister.

Early KCBs

The initial list of civil KCBs was issued by Downing Street in April 1848 (Gazette issue 20850), and reflected both foreign and home services. The first recipient was Henry Bulwer, the envoy to Spain, who received the honour along with the envoys to Brazil and the United States of America. There were places for the governors of Bombay, British Guiana, Labuan and New Zealand, and officers of the Bengal and Madras Artillery. The home knights were led by Charles Trevelyan, the assistant secretary to the Treasury, who was followed by officers from the Admiralty and the War and Colonial Department.

One of original recipients was Rear-Admiral Francis Beaufort, the hydrographer to the Admiralty, after whom the Beaufort wind speed scale is named. The other early science and engineering recipients include:

- Benjamin Baker, the civil engineer responsible for the Forth Bridge

- George Darwin, the astronomer and son of the naturalist Charles Darwin

- William Jenner, the physician

- Roderick Murchison, the geologist

- John Murray, the oceanographer

The early KCBs from other areas of endeavour include

- Thomas Brock, the sculptor of the Victoria Memorial at Buckingham Palace

- Rowland Hill, the postal reformer and pioneer of the Penny Black

- John Macdonald, the prime minister of Canada

- Leslie Stephen, the editor of the Dictionary of National Biography

- Edward Walter, the founder of the Corps of Commissionaires

The use of the civil KCB for envoys and governors, and for work associated with British India, largely died out by the end of the 19th century, because of the introduction of alternative honours. In the case of envoys and governors, the change came about from the late 1860s when the Order of St Michael and St George was dedicated to overseas services. Similarly, in India the civil knighthood of the Bath was overtaken by awards in the Orders of the Star of India and the Indian Empire.

There was no requirement that candidates for the knight/dame commander class must already hold the third class, although in practice 70% of the 1,100 or so individuals who have been appointed a KCB or DCB to date received the CB at an earlier point in their career. There were also promotions from second to first class, and since 1847 around 180 of the KCBs progressed to GCB.

Civil Service

The principal use of the civil KCB was to reward work in the public service, usually in departments of state, and at the level of permanent secretary. Almost 70% of recipients were civil servants who managed organisations that dealt with a range of activities, which extended from agriculture, food and the environment, to education and health, as well as trade and transport. Some of the departments that regularly featured in the KCB list include the Treasury and Revenue and Customs, and the Ministry of Defence and its Admiralty, Air Ministry and War Office antecedents.

More than 50 KCBs were officers whose duties at the Palace of Westminster were central to the orderly conduct of government business, including the clerk of the House of Commons, and the clerk of the Parliaments. The KCB register also provides an insight into the evolution of state organisations, with grants to officials in departments that no longer exist, such as the war-time ministries of Aircraft Production and Munitions, and the department of Prices and Consumer Protection. The smaller bodies that appear in the register include the British Museum, National Portrait Gallery and Royal Mint, together with the Medical Research Council and the University Grants Committee.

The knighthood of the Bath was conferred on several commissioners of the Metropolitan Police, including Charles Warren who led the Victorian force during the era of the Jack the Ripper murders. Several civil knights came to public notice, as with Richard Solomon, the agent-general of Transvaal, who presented the Cullinan Diamond to Edward VII in 1907 on behalf of that colony, and Hay Donaldson, the chief technical adviser to the Ministry of Munitions who drowned with Lord Kitchener and more than 700 other men when HMS Hampshire sank on its mission to Russia in 1916.

There was also the case of Sir Frederick Atterbury, the controller of the Stationery Office, who attended a war-time event during which his colleague highlighted a grievance against the King’s enemy that was relevant to readers of The Gazette:

“as the only copy of the first issue of The London Gazette is in Germany at the present time. We were invited to send things to the great exhibition in Germany before the war, and we sent No 1 of The Gazette. We hope some day to see that copy again, but we have our doubts.”₁

The use of the civil KCB altered during the war against imperial Germany, because of the creation of the Order of the British Empire in 1917. After that, several holders of the CB were appointed as a knight commander of the British Empire (KBE) rather than being promoted to KCB, although some later gained the senior star.

Many civil knights entered the Bath towards the end of their official employment, while others, such as Keir Starmer, pursued a variety of careers after joining the order. Examples include James Grigg, then chairman of the Inland Revenue, who was invested with his KCB insignia on 23 February 1932 and who, on the same day a decade later, received the seal of secretary of state for war, as Winston Churchill brought him into the war-time government after the fall of Singapore.

Another KCB who built a second career was William Beveridge, who was knighted in 1919 for his war-time services at the Ministry of Food (Gazette issue 31099). He was later the director of the London School of Economics, and subsequently entered Parliament, where he became the leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Lords. Beveridge is probably best remembered for his part in writing the 1942 government report about social insurance, which helped to inform the creation of the post-war welfare state.

The first woman to join the second class of the Bath was Mildred Riddelsdell, the permanent secretary at the Department of Health and Social Security, who received the civil DCB in 1972 (Gazette issue 45554). The same process of allocating honours applied to women, with awards usually being limited to senior civil servants. The DCBs include two directors-general of the Security Service, Stella Rimington and Elizabeth Manningham-Buller, as well as Alison Saunders, who succeeded Keir Starmer as director of public prosecutions.

Director of Public Prosecutions

The office of Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) has existed under a variety of structures since the late Victorian period, and the level of responsibility attached to that office has always been officially recognised with the grant of a state honour, although not always at the level of KCB.

Three of Sir Keir’s predecessors joined the second class of the more junior Order of the British Empire, with the KBE being conferred on Theobald Mathew in 1946 and Norman Skelhorn in 1966, and the DBE on Barbara Mills in 1996. There was then a further step down the honours ladder for two more recent DPPs, as no more than the plain honour of knight bachelor was approved for David Calvert-Smith in 2002, and Kenneth Macdonald in 2006.

Few DPPs gained further honours after their KCB, with the notable exception of Hamilton Cuffe who received his Bath insignia from Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle in 1898, a few months before he inherited the Irish earldom of Desart. Lord Desart was later given a United Kingdom barony, and in 1919 he was one of the last peers to join the Order of St Patrick.

Armed Forces

Around 10% of the civil knights were connected to the armed forces. The sequence began in 1881 with a statute that allowed the civil honour to be granted to those who “by a lengthened service in command of a regiment of our auxiliary forces, or brigade or our Naval Artillery Volunteers, or as an officer of our Royal Naval Reserve, have contributed in a marked degree to the efficiency of such regiment, brigade or reserve.”

An early beneficiary under the 1881 regime was Robert Loyd-Lindsay of the Berkshire Rifle Volunteers, who was one of five civil KCBs who won the Victoria Cross. Another notable armed forces knight was Henry Hozier of the Kent Royal Garrison Artillery (Gazette issue 27568), who secured the Iron Cross during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and was the father-in-law of Sir Winston Churchill.

The armed forces presence in the civil division was extended in 1892 to include exceptional service in connection with the War Department “otherwise than on active service in the field”, and in later years the qualification for admission was revised to reflect structural changes in the armed forces. The statutory provisions relating to the KCB and armed forces were discontinued in 1948.

A few individuals received the insignia of both the civil and military KCB. The 1847 statute said that members who were admitted to a higher class of another division would “be entitled to retain and wear the insignia of such inferior class, in addition to the insignia of such higher class, although by the acceptance of such higher rank in the said order he shall have vacated his place as a member of such lower class thereof.”

The “inferior class” rule applied to several knights, including another holder of the Victoria Cross, Dighton Probyn, who earned his VC during the Indian Mutiny. Probyn was the subject of a unique progression through the order’s classes and divisions. He was gazetted as a military CB in 1858 while an officer in the Bengal Army (Gazette issue 22154), and advanced to civil KCB in 1887 for his work as comptroller to the Prince of Wales (Gazette issue 25712). Sir Dighton later served as keeper of the Privy Purse, and received his civil GCB in the coronation list of 1902 (Gazette issue 27453). He then gained promotions in the military division, for no apparent reason other than his personal standing with the sovereign, becoming a KCB in 1909, and obtaining the first military GCB of George V’s reign in 1910.

Other roles

Probyn’s civil knighthood of 1887 was one of a series of awards that were approved for members of the Royal Household. During Elizabeth II’s reign such grants were generally limited to the sovereign’s private secretary and some, but not all, holders of the offices of keeper of the Privy Purse and Garter king of arms.

Outside this select group, the Queen also conferred the KCB on Sir Edward Ford (Gazette issue 44210), her assistant private secretary, and the author of the “annus horribilis” letter she referred to in her 1992 Guildhall speech, in reflecting on that year’s fire at Windsor Castle, and other adverse family events. Sir Edward was invested at Sandringham House on 18 January 1967 (see image).

The civil KCB was designed for use by ministers in the United Kingdom until 1975, when provision was made for up to three (of the then 123) civil knighthoods to be conferred on the recommendation of the appropriate minister of state of any member of the Commonwealth “the government whereof shall so desire”.

The only award to be made under the Commonwealth rule was to Brian Talboys, the deputy prime minister of New Zealand, who was noticed in 1991 (Gazette issue 52564). It is unlikely that further recommendations will be made by ministers in any of the sovereign’s overseas realms, given the introduction of comprehensive honours systems in nations such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

Administration

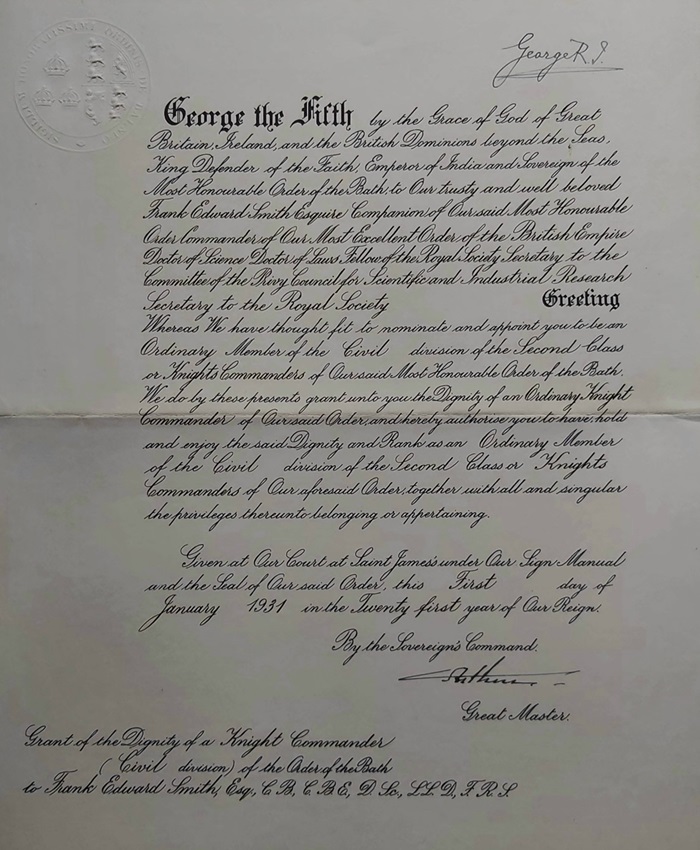

Appointment as a civil KCB was made by warrant under the royal sign manual, sealed with the seal of the order, and countersigned by the great master. The document was usually signed by, or stamped with a facsimile of the signature of, the sovereign and the great master, a senior position in the order that has been filled by six princes since the civil division was introduced in the Victorian era, consisting of Prince Albert (1847-61); Edward, Prince of Wales (1897-1901); Arthur, Duke of Connaught (1901-42); Henry, Duke of Gloucester (1942-74); Charles, Prince of Wales (1974-2022), and William, Prince of Wales (2024-) (Gazette issue 64378).

Grants of the honour were recorded in The Gazette, with the exception of the few honorary awards that were approved after about 1910. The names of the recipients of appointments and promotions were usually announced as part of the routine half-yearly honours list process.

The KCB insignia has been of a similar style since the 1847 statute ordained that the badge, which was to be worn around the neck from a red riband, “shall be of an oval shape, composed of a rose, thistle, and shamrock, issuing from a sceptre between three imperial crowns, the whole pierced and surrounded by the motto, “tria juncta in uno,” all gold”. The star, which was worn on the left breast, was “composed of four rays of silver, between each of which shall issue a smaller ray, also of silver, in the centre, on a ground argent, three imperial crowns, one and two or, within a circle gules, inscribed with the motto, “tria juncta in uno,” in letters gold.”

The first investiture of civil knights was performed by Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace on 6 May 1848, but the event was not gazetted, in contrast to the custom for many of the earlier Bath ceremonies. The presentation of insignia usually took place at a royal residence in London or Windsor, and was often reported in the Court Circular, until that practice ceased in 1939, with the result that there is no published account of the ceremony at which Keir Starmer received his badge and star. A small number of investitures were noticed in the Court Circular after 1939, as with Sir Edward Ford’s trip to Sandringham.

A small version of the KCB badge could be worn by civil knights on appropriate occasions. The illustration below shows the miniature badge and other medals worn by Lord Harlech, the lord lieutenant of Merioneth and chairman of the Shropshire Territorial Army Association, who received his insignia from Edward VIII in February 1936 (Gazette issue 34238).

Sir Keir Starmer and other members of the order enjoy a variety of heraldic privileges. In the case of the KCBs, this amounts to the ability to “surround their armorial ensigns with the circle and motto of this order, and with a representation of the badge suspended thereto”. The knight and dame commanders who were promoted to GCB gained further rights, and some of the civil grand crosses were allowed to erect heraldic plates that remain as a permanent memorial in the order’s spiritual home in Westminster Abbey.

One example of this heraldic journey through the order involved Sir Frank Smith, whose KCB warrant was illustrated earlier. He was made a CB in 1926 as director of scientific research at the Admiralty, and then promoted to knight commander in 1931 as secretary of the committee on Scientific and Industrial Research (Gazette issue 33675), and to GCB in 1942 as controller of telecommunications equipment at the Ministry of Supply. He was later assigned a coat of arms, which enabled him to set up his heraldic memorial in King Henry VII’s Chapel after being installed in Westminster Abbey in 1951. Smith’s arms with his Bath insignia are shown below.

Some of Frank Smith’s colleagues received other distinctions that recognised their professional achievements, as with the grant of the Nobel Prize to:

- the atmospheric physicist Edward Appleton (who received his KCB as secretary of the committee on Scientific and Industrial Research)

- the nuclear physicist John Cockcroft (scientific adviser, Ministry of Defence)

- the chemist William Ramsay (professor of chemistry, University College London)

- the physician Ronald Ross (professor of tropical medicine, Liverpool University)

The prestigious distinction of membership the unreformed Order of Merit was conferred on seven of Sir Keir’s predecessors as civil KCBs:

- the diplomat and war-time administrator Alexander Cadogan (permanent secretary, Foreign Office)

- the art historian Kenneth Clark (director, National Portrait Gallery)

- the diplomat and public servant Oliver Franks (permanent secretary, Ministry of Supply)

- the geologist Archibald Geikie (director-general of the Geological Survey)

- the astronomer William Huggins

- the engineer of the steam turbine Charles Parsons

- the zoologist Solly Zuckerman (chief scientific adviser, Ministry of Defence)

Politics

The civil knighthood was rarely granted to politicians, although the more senior grand cross was occasionally allocated to prominent parliamentary figures, as evidenced by the award to Henry Campbell-Bannerman, who was given his GCB in 1895 as part of Lord Rosebery’s resignation honours list (Gazette issue 26639), after serving as secretary of state for war.

A political dimension was introduced to the KCB in the 1980s, when the honour was conferred on John Nott, who was defence secretary during the Falklands campaign of 1982 (Gazette issue 49235).

No modern political use has been made of the GCB, but the Nott precedent was followed in 2016 when David Cameron’s resignation honours list included a KCB for the defence secretary Michael Fallon (Gazette issue 61678). The same honour was later approved for David Lidington, the chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and for David Davis, the secretary of state for exiting the European Union.

Three more political awards were announced in Rishi Sunak’s dissolution honours list in July 2024, which brought the KCB for the deputy prime minister Oliver Dowden; the Northern Ireland secretary Julian Smith, and the defence secretary Ben Wallace (Gazette issue 64480).

A few of the civil knights had family connections with prime ministers, in addition to the Hozier link with Churchill’s father-in-law that was mentioned earlier. The KCB register includes Lord Palmerston’s brother, the diplomatist William Temple, and Lord Rosebery’s cousin, Henry Primrose, the chairman of the Board of Customs.

The more senior civil grand cross was held by the brothers of Lords Derby, Liverpool and Melbourne, and was also conferred on the sons of George Canning, William Gladstone and Sir Robert Peel: Charles Canning as governor-general of India after the mutiny; Herbert Gladstone on retiring as the first governor-general of the Union of South Africa, and Robert Peel Junior as chief secretary for Ireland.

Sir Keir Starmer did not wear his Bath badge and star or miniature at Buckingham Palace on 25 June 2024 when, as leader of the Opposition, he attended the state banquet for Emperor Naruhito of Japan, an event at which insignia was worn by the majority of the King’s other guests. It is a matter of conjecture, although one of little political significance, as to whether the new prime minister will give his civil KCB a more prominent place in public affairs during the course of his premiership.

About the author

Russell Malloch is a member of the Orders and Medals Research Society and an authority on British honours. He authored Succession to the Crown: From Charles II to Charles III, which explores the coronations, honours and emblems of the British monarchy.

See also

King Charles III and The Gazette

The Order of the Garter and Queen Elizabeth

The history of the George Cross

What are the Dissolution Honours?

Find out more

Succession to the Crown: - From Charles II to Charles III (TSO Shop)

Images

Russell Malloch

Russell Malloch

Russell Malloch

Russell Malloch

Russell Malloch

Russell Malloch

Russell Malloch

References

- The Times, 14 June 1918, page 3.

Publication date

12 August 2024

Any opinion expressed in this article is that of the author and the author alone, and does not necessarily represent that of The Gazette.