Demise of the Crown: #13: Chapels and memorials

As the official public record since 1665, The Gazette has been recording the deaths of monarchs for over three centuries. As part of our ‘Demise of the Crown’ series, historian Russell Malloch looks through the archives at The Gazette’s reporting of Victorian chapels and memorials.

Albert memorials

Shortly after the death of the Prince Consort, the Queen and her children took steps to create a shrine to Albert within the walls of Windsor Castle, in addition to the ongoing work on the mausoleum at nearby Frogmore.

A cenotaph for the prince was created within the Tomb House or Wolsey Chapel, which lay immediately to the east of St George’s Chapel, and above the area that was excavated during George III’s reign to create the royal vault, which now contained the remains of the last three Hanoverian kings, and other members of the royal family.

Meanwhile, public funds were being raised that allowed supporters of the monarchy to pay their respects to the prince’s memory, which would take the form of a golden statue of Albert in his Garter robes.

The design and decoration of the new chapel for the Prince Consort at Windsor was entrusted to the architect Sir Gilbert Scott, the sculptor Henri de Triqueti, and others. The result was an ornate temple that was decorated with religious panels, and at the centre of which stood an elaborate cenotaph displaying a recumbent effigy of the prince in armour, rather than his Garter robes.

The building was later re-named the Albert Memorial Chapel and was opened to the public in 1875. It was, however, a place that became one of increasing sorrow for the Queen and her family, as Victoria lived long enough to see it house the tombs of her son Leopold, Duke of Albany, and her grandson Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence.

Gilbert Scott was also the architect of the most famous of London’s monuments to the Prince Consort, which was located in Kensington Gardens and consisted of what Scott described as “a colossal statue of the prince, placed beneath a vast and magnificent shrine or tabernacle, and surrounded by works of sculpture illustrating those arts and sciences which he fostered and the great undertakings which he originated”. The style of Albert’s memorial was derived from the monument to the author Sir Walter Scott that was erected in the centre of Edinburgh in the early 1840s.

The Albert Memorial took many years to finish, and the public was given access to the Gothic structure in 1872. Because of the death of the original artist, it was not until 1876 that the gilded statue of the prince, seated in his Garter robes, was revealed under its ornate canopy. The statue showed Albert holding a book inscribed “Great exhibition of the works of industry of all nations” and so recalled his role as a member of the royal commission that was set up in 1850 to inquire into the industrial showcase, which the Queen opened in May 1851 (Gazette issue 21208).

Victoria was evidently pleased with the progress on the Albert Memorial project, even before her husband’s Gartered statue was in place, as The Gazette recorded that she conferred the honour of knighthood on Gilbert Scott at Osborne in the summer of 1872, soon after the memorial was opened to the public (Gazette issue 23886).

Duke of Kent

Given the absence of statues or memorials to the last three Hanoverian kings, either in or near St George’s Chapel, it is notable that Queen Victoria sanctioned several additions to be made to the fabric of Windsor Castle, as well as setting up memorials to a man who never wore the imperial crown, even so cherished a prince as Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

The Queen approved further changes to St George’s to mark the lives of two knights of the Garter who were near relations, as she placed a monument to her father Edward, Duke of Kent, in the south nave in 1874, and five years later a statue of her uncle Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, later king of the Belgians, was erected at the entrance to the north nave.

The Duke of Kent’s alabaster sarcophagus was decorated with his insignia as a knight of the Garter, St Patrick and Bath, while the white marble effigy was by the sculptor Joseph Boehm and showed the duke in his robes. The Kent memorial remained in the chapel until 1953, when it was removed and taken to Victoria and Albert’s mausoleum at Frogmore.

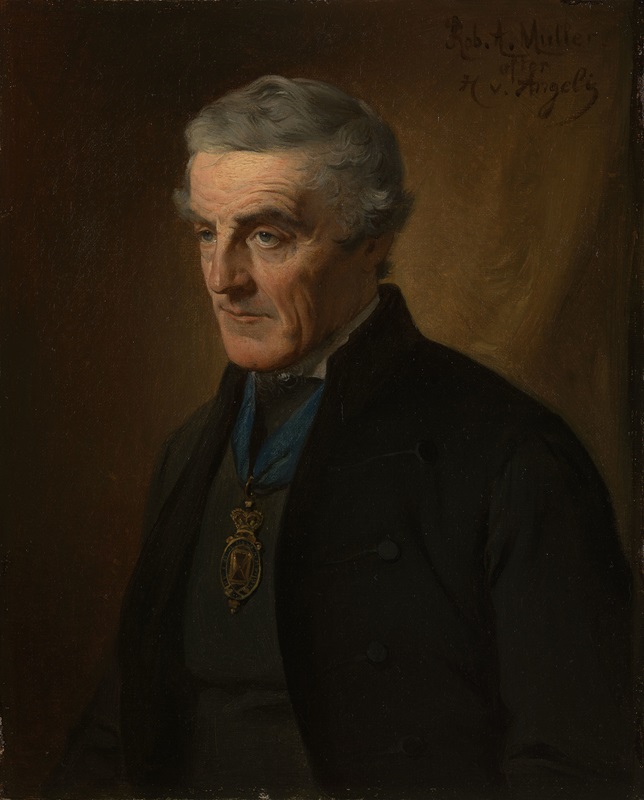

The monument to King Leopold was mentioned earlier in connection with the death of his first wife, Princess Charlotte of Wales, in 1817. The Victorian statue stood outside the Urswick Chapel, which housed the memorial to Charlotte and their child, and portrayed the Belgian king wearing the mantle of the Garter, of which he was one of only three knights with two plates in the stalls in St George’s Chapel, one as a prince of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and one as king of the Belgians.

The Queen had a special relationship with her uncle Leopold, and The Gazette of 1865 announced that the Belgian monarch would be granted both a court and general mourning (Gazette issue 23048). A common descent of Victoria and Leopold from the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld also helps to explain the mourning notices that were issued for two of Leopold’s nephews (and first cousins of the Queen), namely Augustus of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in 1881 (Gazette issue 25000), and his brother Ferdinand, the former king of Portugal, in 1885 (Gazette issue 25540). The same family line also led to the otherwise surprising notice from 1867 about the death of the Emperor of Mexico, an Austrian prince who married Leopold’s daughter (Gazette issue 23271).

Prince Imperial

The Duke of Kent and the King of the Belgians had obvious links with St George’s Chapel, where their heraldic plates provided a permanent record of their knighthood of the Garter. There was, however, a much weaker connection between the Garter and a French prince whose tomb now occupies a prominent position at the western entrance to the chapel, on the spot where the Kent memorial stood before it went to Frogmore.

The cenotaph commemorated the life of Napoleon, whose father Emperor Nepoleon III of France joined the Garter in 1855 (Gazette issue 21697), and whose stall plate was among those at Windsor. The French prince never followed his father into the Garter, although he joined several high European orders, including the Danish Elephant and the Spanish Golden Fleece.

Napoleon III and his family lived in England after the fall of the empire, and in 1873 his remains were placed in the church of St Mary at Chislehurst in Kent, where his granite sarcophagus was offered to his widow as a mark of respect by Queen Victoria. The coffin was sometimes draped with the tricolour, and with the emperor’s Garter banner.

The Gazette recorded the court mourning for the last emperor of the French (Gazette issue 23937), having previously noticed measures to lament the passing of members of the House of Orleans, and the black dress code that applied after the execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette in 1793. The Gazette also reported the three weeks mourning for Louis XVIII in 1824, and for King Louis Philippe, who died two years after he was deposed in the revolution of 1848 (Gazette issue 21131).

Napoleon III’s son, who was often styled the Prince Imperial, volunteered to assist with a British military expedition in Africa, but was killed during the operations. The Gazette reported court mourning to mark his loss (Gazette issue 24736), and his body was brought to Kent, where it received a royal reception. In July 1879 the Queen attended his funeral, and the pall bearers included four of Victoria’s sons, as the Prince of Wales was joined by the Dukes of Connaught and Edinburgh, and Prince Leopold.

An appeal for subscriptions to raise a monument to the Prince Imperial’s memory began, and the dean of Westminster consented to the monument being located in King Henry VII’s Chapel, which was the scene of royal burials until the close of the 18th century. In July 1880 the abbey proposal was criticised in the House of Commons, as being likely to impair relations with the French republic. The Queen resented the Gladstone government’s failure to support the Westminster scheme, and Victoria wrote that she was:

“greatly shocked and disgusted at […] the want of feeling and chivalry shown towards the memory of a young prince, who fell because of the cowardly desertion of a British officer, and whose spotless character and high sense of honour and noble qualities would have rendered a monument to him a proud and worthy addition to Westminster Abbey, which contains many of questionable merit.

But where is chivalry and delicacy of feeling to be found in these days amongst many of the members of Parliament. As it is, St George’s will be a fitter and safer place for this monument, which is one of the finest productions of modern art.

The Queen could have wished the members of the government had voted.”₁

Having offered the protection of St George’s, the Queen declared that she would do all she could to prevent any prince, British or foreign, from being buried in the abbey, and indeed no British prince has been laid to rest at Westminster since the death of the Prince Imperial.

In 1881 the Prince Imperial’s monument, which was also by the sculptor Boehm, was placed in the Bray Chapel, one of the chantry buildings within St George’s. Many years later the Bray became a retail shop, and in the 1980s it was decided to relocate the French prince’s cenotaph to the south nave, where it now sits directly opposite the tombs of King George and Queen Mary, where the Kent tomb was erected before it migrated to Frogmore.

The Prince Imperial’s mother, the Empress Eugenie, shared Victoria’s desire to create edifices to grieve for the departed and, after moving her residence from Chislehurst to a new home at Farnborough in Hampshire, she established a church to house the remains of her husband and son. Their bodies were transferred from their initial resting place in Kent to what is now St Michael’s Abbey in 1888, and Queen Victoria sent a wreath, and later visited the resting place of the last French monarch.

Other Windsor memorials

The Prince Imperial’s cenotaph lies close to the many memorials to men who were not of royal birth, but who played an important part in the story of Windsor Castle, and in the services that were organised to commemorate some of the more ordinary knights of the Garter, as well as members of the British and European royal families.

After his death in 1840, a black marble slab was placed in the pavement of the chapel to record the fact that in a vault beneath “are deposited the remains of Sir Jeffry Wyatville, R.A., under whose direction the new construction and restoration of the ancient and royal castle of Windsor were carried on during the reigns of George the 4th, William the 4th and of Her Majesty Queen Victoria.”

The death of Sir Joseph Boehm in 1890 was also recognised, this time with a brass plaque bearing his coat of arms, which explained that “This tablet was erected by Queen Victoria in high appreciation of his talents as a sculptor and in heartfelt gratitude for the memorials his art has left of many who were dear to her.”₂

Boehm’s works in the chapel included the effigies of the Queen’s father, the Duke of Kent, her son-in-law, the Emperor Frederick III of Germany (which was moved to Frogmore in 1950), her uncle Leopold of Belgium outside the Urswick Chapel, and the Prince Imperial in the south nave.

The Boehm and Wyatville memorials took up little space in the limited room that was available within St George’s Chapel, but something much more substantial was done to mark the life of Gerald Wellesley, who was the nephew of the first duke of Wellington, and the dean of Windsor and register of the Garter from 1854 until his death in 1882.

There were recent precedents for deans being remembered at Windsor. St George’s contained a brass tablet in the Rutland Chapel for Henry Hobart, which recalled his 30 years as dean and register from 1816 to 1846, and stated that “during which period it was his office to read the funeral service over three kings of England”. As well as his work for the three kings, Hobart had officiated at the funeral of the Queen’s father in 1820.

Gerald Wellesley attended many investitures of knights of the Garter, including the ceremony for the Prince Imperial’s father in 1855, and he assisted the archbishop of Canterbury at the funeral services for the Queen’s mother and husband. His recumbent effigy by Boehm was executed in white Carrara marble and showed Wellesley wearing his insignia as an officer of the Garter, with his feet resting on a book representing the register of the order.

The Queen unveiled Dean Wellesley’s cenotaph in 1884, while his remains were buried in the Wellington family’s ground at Stratfield Saye in Hampshire. The unveiling ritual was performed by Randall Davidson, one of Wellesley’s successors as dean of Windsor, who later became archbishop of Canterbury, and played a central role at the funeral of King Edward VII in 1910. There are memorials to Davidson among his fellow archbishops in their cathedral at Canterbury, while several of the other officers of the Garter are remembered at various locations throughout England. Wellesley was, however, the last dean to be accorded such an impressive testimonial in his workplace at Windsor.

Succession to the Crown: From Charles II to Charles III

Succession to the Crown is essential reading for anyone with a keen interest in the British royal family and provides an excellent and trusted source of information for historians, researchers and academics alike. The book takes you on a journey exploring the coronations, honours and emblems of the British monarchy, from the demise of King Charles II in 1685, through to the accession of King Charles III, as recorded in The London Gazette.

Historian Russell Malloch tells the story of the Crown through trusted, factual information found in the UK's official public record. Learn about the traditions and ceremony engrained in successions right up to the demise of Queen Elizabeth II and the resulting proclamation and accession of King Charles III.

Available to order now from the TSO Shop.

About the author

Russell Malloch is a member of the Orders and Medals Research Society and an authority on British honours. He authored Succession to the Crown: From Charles II to Charles III, which explores the coronations, honours and emblems of the British monarchy.

See also

King Charles III and The Gazette

Gazette Firsts: The history of The Gazette and monarch funerals

Find out more

Succession to the Crown: - From Charles II to Charles III (TSO shop)

Images

The Gazette

Alistair Laming / Alamy Stock Photo

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2025

Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2025

The Gazette

References

- The letters of Queen Victoria, 2nd series, Volume III (1928), page 119.

- Shelagh Bond, The Monuments of St George’s Chapel (1958), page 19.

Publication date

13 January 2025

Any opinion expressed in this article is that of the author and the author alone, and does not necessarily represent that of The Gazette.